Accrediting Foraging & Wild Food in the UK

Foraging Teacher and Association of Foragers member Mark Williams explores the notion of benchmarking, accreditation and qualifications around foraging and wild foods in the UK.

This article refers to a Wild Food Accreditation Scheme Scoping Report funded by The Association of Foragers and NatureScot, which you can read in full here: Wild Food Accreditation Scheme Scoping Report.

You can listen to Mark talking about the origins, intentions and challenges of the project from 1:06:54 on this podcast.

Browse more blogs on the politics of foraging

Image ©GallowayWildFoods.com

________________________________________________________________________________

Foraging Accreditation: Why?

A significant proportion of foragers are intuitively resistant to complicating foraging with any form of accreditation. Many are suspicious of the sorts of barriers to access, hierarchies and bureaucracy that accreditation might bring. I know I am.

It’s curious then, that I’ve spent long periods over the past 3 years wrestling with the notion of a wild food accreditation scheme for the UK, researching possibilities, and co-authoring a report on the subject, with much input from fellow foraging teachers from the Association of Foragers.

I’m still wondering how this came about. As a mushroom lover, I like the idea of mycorrhiza-like human networks: large numbers of anarchic, curious, exploratory individuals with enough perspectives, paradigms, and communication skills in common, that they don’t need any kind of organisational structure to operate fairly and effectively.

But human networks rarely operate with the same anarchic efficiency as fungal ones, and most people will recognise the difficulty of achieving harmony in even a small family, let alone larger human groupings! This isn’t helped by social media, which seems custom-built to induce people with lots in common to argue about the few things they don’t have in common, and the loudest and most insistent tend to set the tone. (You can read my thoughts on the relationship between foraging and social media here.)

“The tyranny of structurelessness” describes this phenomenon: in human groups and movements where no organisational structure exists, power nevertheless tends to be exerted by interested parties. In such groups, those who shout loudest, or more insistently, tend to have disproportionate influence on its development, yet there is no way of holding them to account.

What does this have to do with foraging?!

Foraging for personal consumption is currently pretty much unregulated in the UK beyond basic laws around access and sensitive species. Commercial foraging requires the permission of landowners and is covered under basic public health regulations around food, but beyond that there are very few checks or barriers to wild harvesting for profit.

As wild spaces come under ever-increasing pressure from multiple directions, and foraging increases in popularity, some voices have started to shout quite loudly into that structurelessness: councils have proposed (then run away from) banning foraging in parks; Forestry and Land England widely publicised (then abandoned) a ban on picking any mushroom in the New Forest; foraging “diplomas” and foraging businesses accrediting their own practices have sprung up without transparent, credible accreditation structures.

Left unchecked and unchallenged, there is a danger that some of these interest groups may come to exert disproportionate influence over public discourse around foraging, without recourse to the many millions of people who actively practice it, and without any agreed benchmarks or consensus around good practice.

Differences of opinion around what constitutes “good foraging practice” are not as polarised as newspapers and social media often suggest. I’ve met a lot of foragers and every one of them considers themselves a ‘nature lover’. Many foragers also work in the field of conservation. Millions of people harvest blackberries, elderflowers and wild garlic every year with very little controversy. There are many examples of conservation organisations recognising and actively promoting foraging as a tool with which to connect the general public with plants, seaweeds and fungi. The scoping report I’m discussing here was part funded by NatureScot – Scotland’s publicly funded “nature agency”, which believes “Connecting people and nature is vital to rise to the challenges of our times and contributing to prosperity and wellbeing”.

Commercial Foraging and Accreditation

The harvesting and use of wild plants, fungi and seaweeds for commercial gain can raise hackles among interest groups – including foragers who only harvest for personal use. Its easy to imagine exploitative practices and vilify “large scale” commercial foraging operations but these tend to be more the imaginings of tabloid newspapers and Facebook rumour, with precious little evidence to support it. A more sensible look at the sector (which is detailed in the report) suggests that the majority of money made from wild harvests is through seasonal piecework, or more often people selling surplus from their personal harvests direct to local businesses. For others, wild harvests are the basis, or more likely a strand, of micro- or nano- businesses, where value is added to abundant harvests. A survey of this growing “sector” is overdue, and researchers at Aberdeen University are due to publish the results of one soon.

Marian Bruce of Highland Boundary, and co-author of the Wild Food Accreditation Scoping Report, got involved because she couldn’t find clear information on responsible harvesting and safe use of the plants she wanted to use in her distilling operation. Most of the questions asked by chefs and producers I consult on wild foods for are around safety and sustainability. There appears to be a clear and pressing demand from commercial wild food harvesters and processors for benchmarking and best practice guidelines. Many of these businesses contribute significantly to rural economies – a key focus of post covid economic recovery strategies.

Image ©GallowayWildFoods.com

Good Foraging Practice: Building Consensus

Everyone who forages, whether for personal use or for profit, ought to be an ambassador for foraging through their embodied practice – reassuring the non-foraging literate, checking in with landowners (even if you aren’t legally obliged to), protecting and giving voice to the habitats and species they forage. But this alone may not be enough. If foragers are to influence wider public attitudes – and ultimately policies – around foraging, they must not only engage with discussions, but place themselves at the heart of them. By actively engaging with other interest groups, they have the opportunity to listen to concerns, bust myths, and resolve conflicts. The only alternative is kicking up a fuss when it’s too late, and this almost inevitably leads to resentment and entrenchment.

Similarly, if other interest groups such as land managers, conservation groups and food standards agencies wish to exert evidenced, meaningful and helpful influence over foraging, they should actively solicit the insights that foragers can bring. As failed foraging ‘bans’ have proven, the right to forage is deeply embedded in UK law and psyche, and foragers are highly unlikely to recognise, understand, or obey directives imposed on a piecemeal basis or without clear and transparent evidence of need.

It isn’t always easy to engage foragers in discussion. Most prioritise time outdoors a long way ahead of sitting at a computer screen. They tend to feel instinctively and passionately that their foraging, far from being problematic, is a positive benefit to the world around them.

If the informal, anarchic, nebulous nature of foraging has made it hard to connect with foragers in the past (though nobody seems to have tried very hard), the formation and growth of The Association of Foragers means that we now have a structure that can give voice to the concerns, insights and interests of experienced foragers who have thought long and hard about the issues.

Image ©GallowayWildFoods.com

________________________________________________________________________________

Principles For a Wild Food Accreditation Scheme

One of the questions I’ve been wrestling with is how to spread helpful information, and accredit good foraging practice without placing barriers between humans and foraging.

A proposed solution arising from the report is a three tier structure of accreditation, developed and overseen by a steering group composed of relevant interest groups.

Key tenets of this proposed Wild Food Accreditation Scheme are that it should be:

- Voluntary. Nobody should ever need a piece of paper to allow them to forage for personal consumption.

- Accessible. It should not impose barriers between any group or individual and legally foraging for personal consumption.

- Inclusive. Developed, administered and overseen by a coalition of interest groups that includes active foragers.

- Educational. Supports and guides learning and best practice. Helpful curriculum and resources should be designed and agreed to promote best practice.

- Evidenced. Built on sound scientific and experiential evidence. As many wild harvests have no history of commercial use, expensive scientific data can be scarce; thousands of years of non-commercial use can also be a rich and dependable source.

- Focussed. Safe, sensitive and sustainable foraging are at its core

- Flexible. General “catch-all” rules around foraging are often insensitive and inappropriate. Accreditation on a granular species-by-species basis will help participants to recognise the distinct sensitivities of individual species, and achieve accreditation in a portfolio of species that is most relevant and appropriate to their needs and interests.

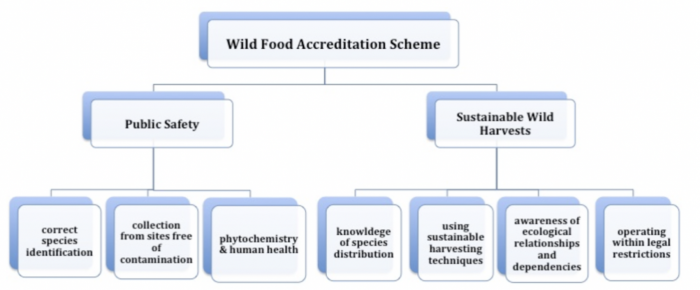

Building Blocks of a Wild Food Accreditation Scheme. Source: Susanne Masters, WFAS Scoping Report

A Suggested Structure for a Wild Food Accreditation Scheme

From the principles listed above, the report suggests a three tier structure applicable to the whole of the UK:

Level 1: Basic engagement.

Online open book multiple choice tests and associated learning resources for the general public, each focussed on individual species.

An encouraging entryway to foraging and a means for participants to learn about and gauge their knowledge around safe identification, safe usage and sustainable harvesting while foraging for personal use. Think of it like a Scout Badge, only for a particular wild harvest! The report identifies 43 plants, 23 fungi, and 15 seaweeds that reflect the species of most interest to most foragers in the UK, and these would be prioritised for L1 Tests.. You can read some sample Level 1 tests in the report.

Level 2: Competence to supply or teach about wild foods for money

In person field assessment by a Level 3 accredited assessor, demonstrating advanced competency in sustainable harvesting and safe use of individual species.

Includes accurate identification of species, communication/terminology, awareness of sources of environmental contamination, sustainable harvesting techniques, legal constraints on commercial wild harvesting, and relevant safety standards in supplying or teaching about wild ingredients.

Level 3: Assessor (of Level 2)

Initially recruitment of individuals that a stakeholder panel agree possess the necessary expertise to assess competency to Level 2 standard. Once up and running, L3 could be achieved by gathering an agreed number of Level 2 accreditations, and a general assessors accreditation.

Next Steps

Although there is still plenty of work to do, this proposed structure seems to me like a sound starting point. But it will be meaningless unless a significant number of interest groups engage with it, contribute to its development, and, ultimately, back it.

I would welcome any feedback, advice and comment from anyone who has read the report and has an interest in the ideas and concepts it raises. In particular, insights from the following groups would be most welcome:

- Active foragers

- Foraging groups

- Foraging educators

- Wild food suppliers

- Chefs using wild foods

- Food and Drink Producers using wild harvests

- Conservation organisations

- Forest School groups

- Botanical, Mycological and Marine Algae – focussed organisations

- Land owners/managers

- Food Standards organisations

Please note that while this project is UK focussed, we’d love to hear about similar projects from around the world, and especially the benefits and challenges that have arisen around them.

Join the Discussion!

A series of in-person and online discussions and talks about the project are planned for 2023. Please keep an eye on the Galloway Wild Foods events page/social media feeds, and the Association of Foragers news feed for updates.

Please join the conversation in the comments section below, or email Mark directly on mark@gallowaywildfoods.com.

3 Comments

I’m all over this!! I do t think it’s right that anyone can just set up a foraging business and lead walks without some sort of check that they are competent, it’s the one good thing about where I’m currently at!

Hobby level, meh if they want to, but will that cause some sort of snobbery I know it all among the hobbyists? The fb groups are bad enough for this lol

100% if you intend to make some sort of financial gain from foraging! Sorry if you can’t commit to doing a few knowledge tests then why should you be allowed! Any other profession needs qualifications why should foraging which is a very niche knowledge set be any different?

Commercial foraging should only be allowed by qualified professionals (yeah people have been doing it for years and know their stuff but plumbers/ electricians/ lifeguards etc have to do regular testing to show their knowledge is up to scratch before you’re allowed to work!

Teaching even more so, if you’re showing the public potentially deadly things you need to be 100% spot on!! And I also think there needs to be evidence checks that people are doing cpd! I will happily hold my hands up and say I don’t know it all!! (Who does???) but I’ve got my face in a book or talking to other foragers learning more and more as often as I can! Yeah the plants etc don’t chance but the discoveries we make about them do (brown roll rim just as an eg off the top of my head!)

I’d love to help be a part of this

This is fantastic to see, I’ve been searching for accredited foraging courses for some time now, and the few I’ve found seem suspiciously short!

I’d love to find out more, and how I might be able to get involved!

I really appreciate the balanced and thoughtful way you have written about this. Although a member of the AoF, and although I’ve never taken a front seat, I have very much positioned myself on the back seat, or even been out side the vehicle with one finger just about hanging on to something,my lack of engagement in recent years has partly been due to an aversion to the associations development into committees and its aspirations to potentially regulate foraging. Nevertheless, the careful and balanced way you have laid out some of the issues makes me feel far more confident and inclined to engage, so thanks for that.