An Introduction to the Mustard/Cabbage/Brassica Family for Foragers

Know Your (Wild) Brassicas!

Foragers don’t need to be fully fledged botanists, but a practical, working understanding of the key characteristics of plant families can be very useful. Tuning in to plant families is the best way to improve your general foraging skills. If you can learn to recognise the shared characteristics of a family group, precise identification for the wild kitchen becomes much easier. Understanding shared features such as leaf shape and flower structure not only narrows down potential ID’s, but helps you know when to be particularly alert to toxic look-alikes. It will also stop you from imagining dangers that aren’t really there, and open up whole new worlds of gastro-botany.

Related Posts:

- Browse Individual Brassica Species

- An Introduction to the Carrot/Apiaceae Family for Foragers

- An Introduction to Seaweeds for Foragers

- An Introduction to Wild Mushroom Foraging

- An Introduction to the Onion/Allium Family for Foragers

- Forager’s Guide to Conifers

Typical cruciferous (4 petalled, cross-shaped) flowers of the brassicaceae

The brassica family is sometimes referred to as the cabbage or mustard family, or in older books as the cruciferae because all of its members have four petalled cross-shaped flowers.

If you can recognise key features of wild brassicas you need never want for tasty and nutritious wild greens. It is a large family, with around 3000 species worldwide, about 100 of which grow in the UK. Everyone will be familiar with cultivated brassicas such as cabbage, brussels sprouts, turnips, rocket and broccoli, but as these have been selectively bred for over 10 000 years, many now bear only a passing resemblance to their wild prototypes. Cultivated brassicas are usually harvested before many of their their key characteristics become obvious, so although we tend to be quite familiar with their edible stages – usually roots and leaves – other characteristics such as flowers and seed pods tend not to be so easily recognised.

Foragers who know their wild brassicas can enjoy a wide range punchy cresses, some large fleshy succulent leaves, tasty flowers, potent seeds and even a few carb-heavy roots, throughout the year.

General characteristics of brassicas

If you have sweated over the carrot family, then you can relax a little with the brassica family – it has no poisonous members growing wild in the UK, though there are, its fair to say, a few that wont be to everyone’s taste. Its not all plain sailing however, as it is quite a variable family in terms of leaf structure.

It is an unfortunate fact of foraging that many plants are past their best for eating by the time all of their identifiable parts have appeared. But if you can tune in to multiple features over the course of a growing season, making the most of what you can confidently identify, you will be primed and ready to pounce on the “prime cuts” (usually the shoots and pre-flowering leaves) when the plants reappear the following year. Thus, the chronology of identifiable parts goes: shoots, basal leaves, buds, flowers, seeds, skeleton (of previous year’s growth). All of these parts of brassicas are edible except the dried-out skeletons.

So here are some general observations that should help you tune in to brassicas…

Flowers

Brassica flowers always consist of 4 petals arranged in a cross formation (hence the old family name “cruciferae”). This pattern is not unique to brassicas and you should be aware of other families that have 4 petals, such as poppies (papaveraceae) and the willowherbs (onagraceae). I’m afraid one feature is never enough to accurately ID something to eat! For the eagle-eyed, most brassica flowers also have 6 stamens – the small reproductive filaments protruding from the centre. Flowers are predominantly white or yellow, though pink hues are not uncommon.

White cruciferous flowers on garlic mustard

Sea kale – a startling good coastal brassica. The pre-flowering “florets” are the ancestor of purple sprouting broccoli

Leaves

Unlike their flowers, leaves of wild brassicas do not follow one set pattern, but some general characteristics can be discerned. Basal leaves tend to grow more or less radially from a central point. This is far from unique to this family, but still a good starting observation.

Scurvy grass basal rosette

Sea radish basal rosette

Later (cauline) leaves grow alternately from flowering stalks. Individual leaves often consist of a central fleshy stem with roughly paired lobes and larger terminal lobe. Sometimes there is just a large terminal lobe that tapers inwards towards the stem base. There is huge variation in leaf size across the family – from small, delicate cresses (cardamine species) to clunking great things like wild cabbage (brassica oleracea) – the mother of all cultivated brassicas – with large succulent leaves.

Basal leaves (L) v Cauline leaves (R) on Garlic mustard

Seeds

Seeds develop and ripen in distinct, often elongated, capsules. These are correctly called seliques. They develop along flowering stems, maturing in succession as flowers open and are pollinated. The maturing seeds are held in the seliques until ripe. When still green, seliques and their contents can make excellent crunchy, peppery eating. As they ripen they harden, and the pungent flavours of the plant become concentrated in the seed – this is what mustard is made from. Some brassicas have rounded or heart-shaped seliques.

Sea Radish siliques

Siliquae of Cardamine impatiens. Small thin siliques such as those of the cardamines ping open as they dry in the sun, flinging their seeds as they do. (Source Wiki Commons)

Habitat

Such is the diversity of the brassica family, that they have colonised most ecological niches. As with many edible wild plants, the best are usually found along edges. By edges I mean the boundaries between dominant species, where fast-growing plants can compete. Thus, field edges (where “weeds” often take advantage of agricultural fertilisers, and may be polluted with pesticides) can be excellent hunting grounds for mindful foragers. Wood edges, riverbanks and marshes are also fruitful. But the two edges at which the UK most excels are likely to be your best hunting grounds for wild brassicas: hedgerows and the coast. Taking a note of habitat will be an excellent weapon in your identification armoury.

Garlic mustard is a hedgerow specialist

Coastal Brassicas

If you want to forage a decent amount of bulky, nutritious leaves quickly, the coast is the place to go. Succulence in coastal plants is an evolutionary response to salt air and exposure and I believe this is often overlooked as one of many reasons why our hunter-gatherer ancestors settled along the coast. They would have had their pick of some choice brassicas, quickly learning to steward the most rewarding crops and developing very early agricultural practices to encourage favourable characteristics. 10 000 years later, nutritionists and gastronomes are returning to the prototypes…

Large quantities of nutritious, succulent coastal brassicas are less common than they once were. Coastal erosion and plant collectors have undermined sea kale in some areas, though it can still be hyper abundant where established.

Species Focus: Wild cabbage (Brassica oleracea)

Wild cabbage leaves

Brussels sprouts, cauliflower, kale, broccoli…they all started here…

These solid plants with woody stems, large, succulent dull green leaves and bright yellow flowers make their living on alakaline coastal cliffs and beaches. I’m sorry to say that wild cabbage is becoming quite scarce in the UK, mostly due to habitat loss. Any foraging of its succulent leaves should be done mindfully, taking only a little from each plant and none at all from isolated specimens.

The flavour of the leaves is as you might expect from an aristocratic cabbage – richer and stronger than most of its derivatives. It ferments well and makes great sauerkraut, or can be cooked as you might any other cabbage, though you may wish to “cut it” with milder greens. You can temper their inherent healthiness by shredding and frying with bacon.

Wild cabbage growing out of sandy coastal cliffs and embankments, Fife

Smell and Taste

It is important to engage all the senses when foraging. Smell, and even taste, can be every bit as useful as sight in identifying a plant. All brassicas share a distinct flavour profile that is best described by the terms mustardy and peppery. This can range from intense wasabi/horseradish “up the back of the nose” mustardy pungency, to the light pepperiness of a white cabbage. These flavours can help to confirm an identification.

Tasting a plant to help with identification should only ever be undertaken when you are certain you have eliminated highly toxic species (eg. foxglove, hemlock water-dropwort, hemlock and wolfsbane) and seriously unpleasant-tasting/burny (eg. lords and ladies) species from your enquiries. Never use taste to help identify anything that exudes a white sap (unless it’s clearly some sort of dandelion or lettuce) – it could well be a spurge (euphorbia species), which will burn your mouth and possibly your skin too.

Sea spurge – Do not taste this plant! It burns!

With these warnings clearly in mind, I would also say that there are very few plants that are life-threatening when tasted sensibly. Taste is often used even by (experienced) mycologists to help identifyy fungi – see my post on this here. I’m not in any way recommending you try this, but I have seen mycologists knowingly taste death cap mushrooms (amanita phalloides) with no ill effect. That is dangerous and foolish showing-off, but it does underline the crucial difference between tasting and eating.

The process of tasting to aid identification goes as follows. Note that the object is not to ascertain whether the plant tastes “nice“! The intention is only to discern characteristic flavours as part of a set of features to aid with identification.

- Crush the plants leaves and stem in your hand and wait a while to ensure your skin isn’t reacting.

- Smell the crushed plants. Find meaningful words to describe your interpretation of the smell. If you find it repellent, trust your senses and stick to visual ID. Equally, bear in mind that just because something smells (or tastes) appealing, that doesn’t mean its good for you. Remember that taste and smell are just tools of identification, and provide no specific information on edibility.

- Tear a tiny piece (less half a square cm) of healthy leaf off the plant and place it on the tip of your tongue. Leave it for up to a minute, noticing any reaction on the tongue or obvious flavour. Spit it out and rinse thoroughly if you notice any unpleasantness.

- If that seems fine, lightly chew the piece of plant with your front teeth and return it to the tip of your tongue, repeating the previous step.

- Spit the whole piece out and add your taste observations to your visual, textural and habitat and general distribution observations.

- Note that the as-yet unidentified plant never passes the front of your tongue, and certainly goes nowhere near your throat!

- Be aware, that anyone can have an allergy to anything they haven’t encountered before. This goes for all foods, not just unidentified plants in the wild. In general however, the brassica family has a low incidence of allergic reactions.

Species Focus: Horseradish (Armorania rusticana)

Horseradish in full flower

Of all the punchy, in-your-face-and-up-your-nose flavours of the mustard family, the root of the horseradish is the most intense. Harvested when in prime condition in October/November, it will have you crying like a baby when you try to grate it to make that English classic, horseradish sauce. Remember, you must have the landowner’s permission to dig up any plant from the wild.

Wild horseradish is common in the south of England but not in the North. In my obsession to find it in SW Scotland, I’ve done many an emergency stop for large dock leaves. The similarity is superficial and you can distinguish horseradish by its large (70 – 100cm) upright, broad, bright green leaves with a crinkled look and “fish-bone” pattern of veins.

An obsession with the pungent roots seems to have resulted in the neglect of the large, green leaves as a food. They are more subtle in flavour, so great for salads and are ideal for wrapping things. Think sushi wrappers with built-in wasabi!

Fermenting cucamelons with horseradish root and wild spices

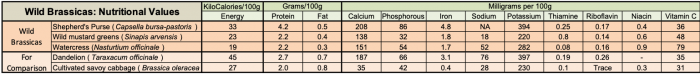

Nutritional Benefits of Brassicas

Most people know that broccoli, cabbage, sprouts and other commonly cultivated brassicas are good for them. As is often the case with wild plants, the nutritional profile of most wild brassicas is superior to their cultivated descendants. When you consider that the flavour of cultivated brassicas has also being diluted, its obvious that agriculture places quantity and convenience over quality. Though in fairness, some wild brassicas are just too pungent for most humans to enjoy (sea rocket for example).

A great deal of money and chemicals goes into eradicating some wild brassica “weeds” that taste considerably better than the crop that is being protected. On a smaller scale, a little brassica “weed” called hairy bittercress (cardamine hirsuita) is often the gastronomic star of my guided foraging walks. Inevitably keen gardeners in attendance kick themselves for the years they have wasted trying to remove it from their garden (an impossible task anyway) – often to make space for far less tasty and nutritious brassicas!

hairy bittercress basal rosettes

Brassica Flavour and Medicinal Geekery

The compounds that give brassicas the mustardy/peppery flavours so appealing to most humans, actually evolved to deter grazing. For the scientists among you, crushing (chewing), the enzyme myrosinase transforms glucoraphanin into sulforaphane. These volatile sulphorous compounds are potent antioxidants that, in the right quantities, have a cleansing effect on body cells. These and other medicinally useful compounds in brassicas, such as carotenoids and indoles, have been found to have potent antiviral, antibacterial and anticancer activity. Whether you are into the science or not, listen to your mother and eat up your brassica greens! They wont necessarily make you better if you are ill, but they will keep you well, and are a cornerstone of a healthy diet.

Some brassicas are relatively high in bitter compounds, which accounts for some of the scrunched faces that brussels sprouts can create! For an extensive discussion of the variation in bitter receptors in humans, see the beginning of my post on making vermouth from wild plants.

sea rocket – super pungent mustard flavour

Getting to Know Wild Brassicas

The best – in fact the only – way to get to know plants is to get out and meet them face to leaf. With a little regular investment of time and observation, patterns and smells I’ve tried to describe here in words, will become obvious. By starting with some easy to ID, common and rewarding species you will quickly be noticing delicious brassicas everywhere.

Start by browsing my posts on individual wild brassica species

You May Also Enjoy:

- An Introduction to the Carrot/Apiaceae Family for Foragers

- An Introduction to Seaweeds for Foragers

- An Introduction to Wild Mushroom Foraging

- An Introduction to the Onion/Allium Family for Foragers

- Forager’s Guide to Conifers

4 Comments

Do you know if the flowers of Aurinia saxatilis (gold dust Alyssum) are edible? PFAF says no edible uses known. Thank you

Sorry, I do not know this plant.

I was wondering if you can eat, Turnip weed/ annual bastard cabbage as I have seen this growing in several places recently and I have read that it is invasive so I thought eating it would be a good idea?

Thank you for this great website!

Vanessa

I’ve never encountered turnip weed personally, but i’m not aware of any members of the brassica family in the UK that are toxic. Some might taste awful though! Do report back…