An Introduction to Seaweed Foraging

How to find, identify, sustainably harvest, preserve and cook rewarding seaweeds

“When the tide is out, the table is set”

Seaweeds are a vast and relatively untapped wild food resource. They are highly nutritious, easy to find, surprisingly tasty and hugely rewarding if you know which to pick and what to do with them. Better still, there are no toxic seaweeds that can be picked on foot in UK waters, so nervous foragers can relax and explore their flavours without fear of poisoning, provided they stay aware of pollution risks. That isn’t to say they will enjoy all that they taste…so I’ve included a guide the most rewarding seaweed species at the end of the article, or if you click the link below or in the pull-down menus above.

There is a deeper dive into all things seaweed, including illustrations, profiles and recipes for to 20 most rewarding species in my book ‘The Coastal Forager” – learn more/order it here.

“…honestly the most beautiful book on wild food – or food actually – I’ve ever seen.” – Liz Knight, author of ‘Forage’, ‘Buds and Blossoms’ and ‘Wild Drinks’.

For an all singing-all dancing guide to seaweed foraging, check out my Seaweed Webinar. The webinar covers everything discussed on this page, plus lots more, including in depth on-location films on key species, recipes, processing tips, a Q&A session, recommended websites and guidebooks and lots more.

“The webinar was amazing! You are a good storyteller. Scientific information, combined with tips and beautiful picturing. 👏” – Kanlenaki on Instagram

“This was absolutely brilliant, thank you so very much for being so generous with your knowledge! The webinar format of videos and live worked fantastically!” – Sarah Hobbs, Webinar chat comment

See also:

Over 700 species of seaweed can be found in UK waters, many of which might be observed without diving. For the gastronomically adventurous there is huge scope for exploratory eating of some lesser known common species, but most of our food interest is focussed on about 20 or so easily accessible and identifiable varieties.

For the purposes of this post, I’ll be focussing on seaweeds that are easy to find and identify, and provide high reward in terms of flavour or nutrition (usually both), without the need for extensive processing or equipment.

Understanding Seaweeds

Seaweeds are properly referred to as macroscopic marine algae, and are divided in to three groups according to pigmentation: green, red and brown. These groups are genetically quite distinct, being the result of convergent evolution, whereby distinct life forms find similar solutions to shared environmental challenges. Be aware that many scientifically red seaweeds can look brown, and many brown seaweeds can look green. You’ll be pleased to hear that most green seaweeds are a vibrant green colour!

The variation in colours among marine algae comes from light-harvesting pigments that have evolved to maximise photosynthesis in different depths of water and levels of light. Thus, the green seaweeds tend to ply their trade higher up the shore, and the brown seaweeds deeper in the sea, though the boundaries are not clearly demarked and there are many exceptions.

Existing in a salty, hostile environment has resulted in a variety of other adaptations: most seaweeds have a solid holdfast or anchor to keep them attached to rocks. Many have developed slippery coatings to allow them to slip freely through potentially destructive waves. These coatings are particularly high in alginates and glutamates – important compounds in the food and medicinal uses of seaweeds as we will explore below. Others that exist higher up the shore have developed strategies for retaining moisture between tides.

Large brown seaweeds are particularly high in alginates to help them ride the surf. Image Source unknown.

Ecological Considerations and Mindful Harvesting Of Seaweeds

Although there are vast amounts of seaweeds around our coasts, we should always remember that complex and important ecosystems are intricately entwined around that abundance. Though they may look like slimy piles of goo when the tide is out, try to treat seaweeds with the same respect you would the plants and trees of a forest or hedgerow, taking no more than you need, and respecting them as food and home for a great many other fascinating and ecologically important species.

In practical terms, this means:

- Never pull seaweeds from the rocks. This is equivalent to uprooting plants – and you don’t get any root! Using a sharp knife or scissors, cut only the top third of any individual growth. This will allow it to regrow.

- Spread your picking around. Pick a little here and there, rather than stripping a whole rock of its jungle. It may be a rockpool to you, but it’s a universe to a shrimp.

- Be mindful of potentially rare species. If you don’t recognise it and it doesn’t seem to be abundant, take only enough for ID purposes – if any. New species of marine algae are being discovered all the time – who knows, you might be able to put your name to one!

You should also consider your own safety:

- Conventional wisdom tells us to gather only live seaweeds that are still attached to the rocks, not those washed up by the tides. Having said this, after a big storm, very healthy fresh seaweeds from deeper waters can be washed up and I see nothing wrong with using your own common sense and judgement on this. Old, decomposing seaweeds are pretty easy to sniff out!

- Be aware of water quality and pollution. Don’t pick from stagnant water, rockpools that aren’t regularly refreshed, busy harbours, fishing ports etc. Also consider general oceanic water quality, the possibility of toxic algae blooms (especially in summer) and background radiation. The Environmental Protection Agency should be able to provide you with good, unbiased information on water quality in your area.

- Most seaweed foraging will take you to some treacherously slippery rocks and unforgiving tides. At the risk of pointing out the obvious, stay switched on, consult tide tables before hand, if in doubt tread between rather than on rocks, seek out non-slip barnacles, and please, please, do sheath your knife/scissors when moving!

Finding Choice Seaweeds

There are very few stretches of coast where there are no seaweeds, but to home in the most rewarding species consideration should be paid to the following factors, which I describe for individual species in the seaweeds species guide:

- General distribution – Where along the coast does the seaweed occur? Most of those I feature on this website have a fairly wide UK distribution and can be quite easily found in the appropriate habitat.

- Habitat – What kind of substrate does the seaweed attach to? Eg. Rockpools, boulders, brackish estuaries or rocky outcrops. This will inform you where to look in terms of the topography of the coast. In general, the biggest variety of good edible species is usually found on steeply shelving rocky coast as opposed to, say, gently shelving sandy beaches.

- Season – Like plants, marine algae have distinct life-cycles, with times of strong growth (characterised by more vibrant flavours and higher nutrient content), reproduction (where it is likely to be weaker and out of condition), and dormancy. Different species follow different rhythms but, in general, January to May are the best times to harvest most seaweeds for the pot. Most spawning occurs May to September. Its unfortunate that this article is due for publication during spawning season, but you should still be able to gather some great seaweed with minimal impact on its lifecycle if you harvest mindfully.

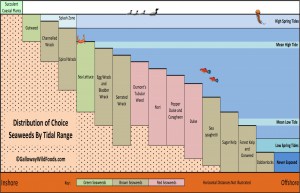

- Tidal zonation – Where in the tidal range does the seaweed grow? Different species are highly specialised to their particular niche. Some can survive with only a splattering of spindrift at high tide, while others need to be fully immersed for almost all their lives, only being exposed to terrestrial foragers at low spring tides. “Spring” in this context refers not to the time of year, but to the elasticity of the tides. The biggest highs and lowest lows usually occur a day or two after a full moon in spring and autumn. Look on tidal zonation as the when as opposed to where of a species. To maximise your chances of the best edible species you should always consult a tide table, and try to time your visit for when the tide is at least half way out. Randomly turning up at the beach often leads to disappointment, like arriving at a free bar when the shutters are down. Its best to follow a receding tide out so you can gather freshly exposed seaweeds, and you’ll also be sure of hitting the lowest point of the tide.

Click on the chart below to see the tidal zonation of choice seaweeds.

- Tidal flow – How strong are the currents, and how exposed is the location? Strong currents and exposed locations can result in bigger, tastier seaweeds due to the higher flow of nutrients in the water. For example, while I find all the species featured on this website along the coast near my home in SW Scotland, the sheltered nature of the Solway Firth means they are about half the size of those I find on the more exposed Atlantic coast. Water temperature influences growth too. Counter-intuitively, most UK seaweeds thrive in colder waters.

To add all this together, the best possible time and place to gather seaweed is on a rocky outcrop on an exposed bit of coast at a super-low April tide. Don’t worry if you can’t manage all of this – foraging is about maximising what’s there, not chasing the unattainable. I’ve found some great stuff in September in sheltered coves.

General Thoughts on How To Cook and Eat Seaweeds

When guiding my coastal forays, I’ve lost count of the number of times I’ve heard words to the effect of, “Oh, I know seaweed is edible, but it’s a bit tough!”

I totally understand this reaction. Many seaweeds have the consistency of rubber gloves. But if you know what seaweeds to look for, when to pick them, and, crucially, how to treat them in the kitchen, your wild larder will take on new dimensions of gastronomy. If you expect to fill a bucket with seaweeds then boil it up and eat it like cabbage, you will be mostly disappointed. Get the right seaweed for the right job.

Later in their season, and especially in more sheltered locations, some species of seaweed – notably dulse, kelps and carragheen – can become home to sea mat (Membrainpora membranacea) which appears as pale crusts on the blades. Close inspection (through a hand lens) will show these to be made up of hundreds of tiny craters which are home to minute tentacled filter feeders. These are harmless, but crunchy and not pleasant to eat. They can be scraped off with the back of your nail, but this becomes laborious if you are harvesting any quantity, so its best to avoid settled specimens if possible.

Seaweeds have, in the past, been much more widely used in the UK than they are now. Unfortunately much of this knowledge has been neglected and forgotten, and some “rediscovery” is required. I also look to Japanese and other eastern cuisines for inspiration. Their long, uninterrupted use of seaweeds has resulted in a close and intimate understanding of how best to use them. Rather than view them only as a “vegetable”, eastern cuisines recognise the flavour enhancing properties of seaweeds that allow other foods to shine. These arise from natural alginates and glutamates that provide umami. This elusive 5th taste sensation (it wasn’t discovered until the early 20th Century, and only recognised in the West in the 1970s), makes us salivate, gets our gastric juices flowing, and adds richness and bass-notes to anything it accompanies. Glutamates are naturally present in many things, notably breast milk, but also meat, shellfish, cheese, fungi, fermented foods and seaweeds.

Glutamates are often added to enhance the flavour of processed foods, thereby saving money on other flavourings, and adding a more-ish addictive quality. This is why its hard to put down a packet of Pringles! These chemicals are seldom good news for your health in processed foods, but are really good for you in their natural state.

This can translate into very “meaty” tasting dishes made using little or no meat, and maximizing the flavours of other ingredients you may have foraged. I have not found a single savoury dish that can’t be improved by the judicious application of the right type of seaweed.

Each variety of seaweed lends itself to particular uses, which are discussed in the species guide, but there are some general approaches to keep in mind:

- If in doubt, dry it out! Most seaweeds dry and reconstitute well, often with an improved flavour. Once dried, they keep almost indefinitely and can be added as a vegetable to wet dishes or be powdered and stored in airtight containers and used as natural stock powders. They make a great base and flavour enhancer for soups and stews, especially combined with dried mushroom powder (which is also very high in umami). Larger seaweeds (such as kelps) can be hung out to dry naturally. More delicate varieties (such as pepper dulse) may need more careful managing. Seaweeds taste better and hold more vitamin D if dried naturally in sunlight, but they can be dried in dehydrator, airing cupboard or low fan oven. Once dry and crisp, store them in well labelled airtight bags or jars – they can be hard to ID when dry and shrivelled! In order to grind seaweeds to a powder, it may be necessary to lightly toast them in a dry frying pan. I use an electric coffee grinder.

Wild stock powder (before shaking) – made with 3 types of seaweed and 3 type of fungi. Delicious – and good medicine too

- Wash seaweeds thoroughly in seawater as you pick them (some of the water-retaining varieties are likely to hold a fair bit of sand), but try not to wash them in fresh water until you are ready to use or dry them (if at all) as this will reduce their salinity and thus their keeping qualities.

- Most seaweeds are (unsurprisingly) salty – make allowances for this in your seasoning. They can provide a healthy alternative to table salt and some even do the job of pepper too!

Medicinal and Nutrtional Benefits of Seaweeds

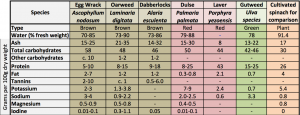

Seaweeds are the most highly mineralized vegetable on earth, accumulating and concentrating minerals directly from the ocean. Research is ongoing into just how bio-available these nutrients are when eaten by humans, but there is little doubt that regular consumption of seaweed is, in general, exceedingly good for us. Some seaweeds (most notably dulse) come closer than any other wild food to providing a fully balanced diet from one organism.

The list of benefits is extensive and well documented online, so a whistle-stop tour of the highlights is all we need here:

- High iodine content supports healthy thyroid function. The thyroid is a gland in your neck that helps produce and regulate hormones. A malfunctioning (underactive) thyroid can result in a wide range of symptoms such as fatigue, muscle weakness, high cholesterol, depression, a higher susceptibility to diseases and difficulty losing weight. One gram of brown seaweed can contain between five and fifty times the recommended minimum daily intake of iodine (red and green varieties provide slightly less). Anyone diagnosed with an overactive thyroid may want to consult their doctor if they intend to eat a lot of seaweed.

- Contain high levels of vitamins A and C, and are also a great source of calcium (higher than broccoli). Red seaweeds in particular can be useful in the treatment of osteoarthritis.

- Potent source of antioxidants and also helps prevent inflammation, and can help the body fight a host of ailments that include arthritis, cancer, celiac disease, asthma, depression, and obesity.

- Help regulate estrogen and estradiol levels – hormones responsible for proper development and function of sexual organs, potentially reducing the risk of breast cancer.

- High protein content – almost as high as legumes

- High levels of soluble fibre, supporting healthy digestion. Seaweed fibre turns into a gel in the gut, slowing down the digestive process and inhibiting the absorption of sugars and cholesterol.

For a more in-depth look at these and more health benefits, see here.

Recommended Further Reading:

- The Coastal Forager, by Mark Williams

- Seaweeds of Britain and Ireland, by Francis Bunker et al

- Irish Seaweed Kitchen, by Prannie Rhatigan

- Extreme Greens, by Sally McKenna

- Seaweed in the Kitchen, by Fi Bird

- The Seaweed Site (http://www.seaweed.ie/)

- Seaweed Na Mara – Blog (http://seaweednamara.blogspot.co.uk)

The Seaweeds

Pepper dulse – Osmundea pinnatifida (&spp)

Pepper dulse – Osmundea pinnatifida (&spp)

Laver (AKA Nori)– Porphyra spp

Laver (AKA Nori)– Porphyra spp

Dulse – Palmaria palmata

Dulse – Palmaria palmata

Sea lettuce – Ulva lactuca and Ulva rigida

Sea lettuce – Ulva lactuca and Ulva rigida

Dumont’s tubular weed – Dumontia contorta

Dumont’s tubular weed – Dumontia contorta

Carrageen/False Carrageen – C. crispus & m.stellatus

Carrageen/False Carrageen – C. crispus & m.stellatus

Sea Spaghetti – Himanthalia elongata

Sea Spaghetti – Himanthalia elongata

Gutweed – Ulva intestinalis & Ulva linza

Gutweed – Ulva intestinalis & Ulva linza

Sugar Kelp – Saccharina latissima

Sugar Kelp – Saccharina latissima

Forest kelp & Oarweed – Laminaria digitata & Laminaria hyperborea

Forest kelp & Oarweed – Laminaria digitata & Laminaria hyperborea

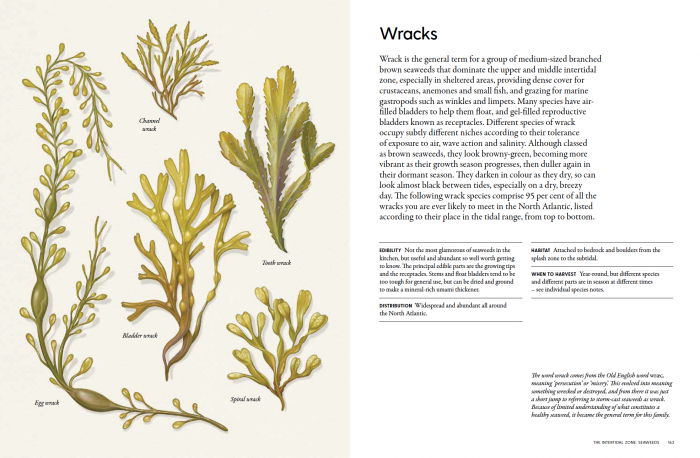

The Wracks: Egg, Spiral, Tooth, Bladder, Channel.

The Wracks: Egg, Spiral, Tooth, Bladder, Channel.

Related pages:

- Seaweed Foraging Guided Walks

- Seaweed recipe: Scottish dashi broth

- Seaweed recipe: How to make sushi with wild ingredients

- Edible Fungi Guide

- Edible Plant Guide

- In season now

For an all singing-all dancing guide to seaweed foraging, check out my Seaweed Webinar. The webinar covers everything discussed on this page, plus lots more, including in depth on-location films on key species, recipes, processing tips, a Q&A session, recommended websites and guidebooks and lots more.

“The webinar was amazing! You are a good storyteller. Scientific information, combined with tips and beautiful picturing. 👏” – Kanlenaki on Instagram

“This was absolutely brilliant, thank you so very much for being so generous with your knowledge! The webinar format of videos and live worked fantastically!” – Sarah Hobbs, Webinar chat comment

14 Comments

What a wonderful website you have. I am a seafood veteran from Maine (USA) and spent 20 years buying sea urchins which had built up in such numbers that most of the kelps and other edible seaweeds were

gone. It took us about 10 years with 2500 divers to bring back the kelps and collapse the urchin fishery.

Now, Maine is trying to ramp up seaweed industry and I am contemplating whether to farm or harvest wild

products. My connections in Japan will not pay the going prices for laminarias so I am looking at

domestic markets. Is it true that sea lettuce is the favorite edible seaweed in Europe? Here in Maine

the lobster industry rules and they want kelp beds left alone as habitat for juvenile lobster. Since we

cleaned up most of the urchins, lobster landings have been huge. We could have had a sustainable

urchin fishery but the urchin barrens that existed in the 1980’s was not a diverse biological environment.

Now we have lots of seaweed and lots of lobster. Warming water in the Gulf of Maine is a concern but

those farming laminaria are having trouble with quality because of biofouling and locating farms in

convenient areas that are not conducive to high quality kelp. Are you in the aquaculture end of the business? I have heard that the Norwegians are permitting many new seaweed farms now.

Sir/Madam, great site.

As sources for us inlanders are very sparse, I would like advice on freeing or otherwise storing. Also a few simple recipes would help here or reference to some, especially as added to ordinary or traditional meals

I run a few non commercial lobster traps in the Cape Cod canal and have been curious about the various seaweeds I find in and around the traps. I often thought I’d like to take a bit to complement the lobster, or perhaps when lobster is scarce. This site gives me some enthusiasm to try. Thanks

Amazing and enlightening, thanks!

Any opinions or advice on which seaweeds make the best salt substitute?

Hello guys,

I am living in North Queensland, Australia. I am just beginning to learn to forage for seaweed. I have found some seaweed but I cannot figure out what it is. I am also a little concerned whether it’s ok to eat because it has encrusted bits on it, which I am thinking might be the beginnings of coral or perhaps the eggs of some other creature. (Offshore from our beaches is the Great Barrier Reef.) Could I please send you some photos? Could you help me please?

Kind regards

Clare

Hi Clare, Some seaweeds can become home to sea mat (Membrainpora membranacea) which appears as pale crusts on the blades. Close inspection (through a hand lens) will show these to be made up of hundreds of tiny craters which are home to minute tentacled filter feeders. These are harmless, but crunchy and not pleasant to eat. They can be scraped off with the back of your nail, but this becomes laborious if you are harvesting any quantity, so its best to avoid settled specimens if possible. You can email me photos, but please first read my guidance here:

Best wishes,

Mark

Wonderful content and informative .

Can you suggest the most neutricious moon phase to cut seaweed for drying and adding to most foods as an enhancer . Is it just before spawning in January to May full or new moon . Many, many thanks Daphne

Thanks Daphne.

Sorry, no idea on this, but remember that seaweeds are not homogenous and each species has its own cycles.

Mark 🙂

Your site is an inspiration and I love it . Thank you . Daphne

Thank you so very much.

So glad I’ve found you……..I now know a little about seaweed and will take my grandkids foraging. Thank you.

Still have a lot to learn….might not have enough years left!

What I loved about this piece is how it managed to balance practical knowledge with a sense of reverence for the shoreline. The way you described harvesting with scissors instead of pulling felt like more than just a tip, it came across as a reminder that seaweeds are part of a wider living system, not just ingredients waiting to be taken.

The sections on tidal zones and seasonal rhythms brought the coast to life in a new way. Suddenly, the rocks, the shifting water, the timing of low tide, all become part of the story of what ends up in a pot or on a plate. It’s the kind of detail that changes how you walk along a beach, because you start to see food and habitat intertwined.

we hold onto that idea of rediscovery. Seaweeds once played a much larger role in diets here, and guides like this show how we can bring them back, not just as something unusual to try, but as a natural and sustainable part of everyday cooking.

This wasn’t just a guide to identification and cooking, it was an invitation to pay attention, to forage with respect, and to taste the coastline with fresh eyes.

Fantastic site

Absolutely educational.I’ve been reared but the sea side, would be familiar with just a few of the various types and which zones to pick them from.

Small gardeners would always harvest seaweed immediately after a storm to use as garden vegetable fertilisers.

Thank ayou