Forager’s Guide to Conifers

Coniferous trees are easy to find in most parts of the temperate and sub-arctic world, and often come in huge numbers. They are the boreal lungs of the earth, and also a hyper-abundant source of food and flavour. In the UK, and across much of their geographic distribution, with the exception of highly poisonous (though easily recognised) yew trees, there isn’t too much that can go wrong when foraging conifers – even for novices. Compared to other areas of foraging, provided you stick to general, common sense protocols around eating a new food, they are pretty low risk and high reward.

Note: This post is written for UK foragers. While much of the information it contains is also applicable elsewhere in the world, non UK readers should also conduct more localised research.

The flavour chemistry of conifers is interesting. Compounds called terpenes (in particular limonene and pinene) are present in most conifers, including “christmas trees”, plantation sitka spruce, and in familiars garden conifers such as rosemary. These compounds contribute delicious flavours of citrus, tannic “piney” zing, and more complex flavours to all kinds of foods and drinks. Read more about them below.

Please note that with over 600 different species of conifer worldwide, it isn’t possible to cover every aspect of this amazing and ancient group of plants in one post! But I hope this is plenty to get you started….

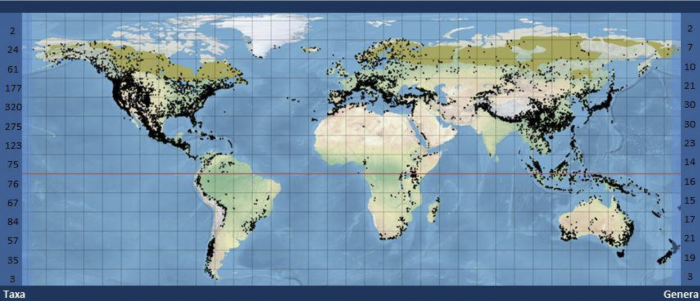

Distribution of conifers around the world. The Y axis on the left indicates the number of species at different latitudinal heights, while the Y axis on the left indicates the number of genera at different latitudinal heights. Photo credit: https://herbaria.plants.ox.ac.uk/bol/conifers

The guide below is designed to help you safely connect with the most common types of conifer in the UK, and start to explore their uses in the kitchen and bar.

More Forager’s Guides:

- Introduction to Seaweed Foraging

- Introduction to the Carrot/Apiaceae Family for Foragers

- Introduction to the Mustard/Brassica Family for Foragers

- Introduction to the Allium/Onion Family for Foragers

- Introduction to Fungi Foraging

Recognising and Avoiding Yew Trees

If you want to play with conifers as food and drink, start by learning to recognise and avoid yew trees (Taxus baccata), which contain high levels of seriously toxic taxine alkaloids in every part except the orange flesh of their ‘berries’. Even the smoke from burning yew is toxic, and a furniture-maker friend of mine once got quite ill from working with it – especially from sanding it down. Eating just a few leaves can make a small child severely ill and there have been some deaths linked to yew poisoning.

Its not all bad news – compounds are commercially harvested from yew foliage and used in modern medicine as anti-cancer drugs (but this is certainly not a treatment to undertake without expert medical supervision!)

I often get asked if I have ever poisoned myself with a foraged plant. I haven’t, but did have a near miss when I carelessly nibbled some yew! Read about my accidental ingestion of yew needles here.

Yew trees are often found in and around graveyards in the UK. Also commonly sculpted into ornamental hedges

Look for yew trees in graveyards, parks, wood edges and sculpted garden hedges, where their bright orange fruits (technically these are not fruits but arils) can be quite distinctive in the autumn. While yew tends to grow squat and dense from trimming in gardens and graveyards, they can grow up to 20 metres tall and really sprawl in parks and woods. They are the longest lived tree in the UK by some way – with 1000 years old being scarcely middle aged. The oldest tree in the UK is thought to be the Fortingall yew, which is estimated to be at least 2000 years old.

Yew trees can grow very old and create large arbours from multiple trunks within their foliage. This was my gang of mentees preparing for the inaugural Scottish Wild Foods Festival – all super excited about setting up a wild cocktail bar in the arms of this beautiful yew at Cardross Estate, Perthshire.

Yew – highly toxic, except for the berry flesh

Oyster plant leaves with yew berries and sea buckthorn

As the fruits of yew aren’t always present, you should also learn to recognise its deep green, short, flattened needles that grow along either side of its twigs. This needle arrangement also occurs on some very tasty varieties of fir (see below), so be extra careful when harvesting those. Yew needles tend to be shorter and always lack the distinctive pair of parallel silver lines on their underside. The underside of yew needles are nowhere near as glamorous, just a drab green that is noticeably less glossy than their upper surface, with a hint of a raised central vein. If you look very carefully at certain times of year you may discern a hint of slightly paler parallel lines on yew needles, but they are never obvious and never silver as on firs.

Yew & Non-yew!

The undersides of yew needles(top – drab green) v the underside of fir needles (bottom – always with two parallel silver lines)

Yew needles are probably most similar to the shortish needles of Western Hemlock (Tsuga heterophylla), so be extra extra careful to observe their silver tramlines and citrussy aroma if you are harvesting from western hemlock needles. Yew needles, when given the “rub & sniff” test I outline below, are pretty much odourless, and certainly lacking in the intense citrus and pine aromatics of edible species. So your culinary as well as your survival instincts should help to keep you safe!

Yew needles underside (left) and top side (right)

A Note on Cypresses

In the UK and Western Europe, once you have mastered yew trees, you can really relax and enjoy all other needled conifers without the necessity to accurately identify them right down to species. I say needled conifers, as I recommend being more circumspect about eating any of the cypress (Cupressaceae) family of conifers, that are characterised by scaly, flat, coral-like greenery, rather than true, distinct needles. Check out the differences here.

Cypress foliage – note that they do not have true needles. Although not known to be toxic, I tend to avoid them as they can be strongly allergenic

Most common of these in the UK is leylandii (Cupressus × leyland), which is often used for hedging or wind-breaks because of its fast-growing, dense foliage. Although juniper and redwoods fall within this family and have some great edible uses, Cupressaceae species tend to be more allergenic than needled conifers. My dad used to come out in a terrible rash when trimming back an ornamental cypress in our garden, so I guess that i’m especially wary.

Certainly there is a long and happy tradition of drinking cedar tea (especially Western Red Cedar) in moderation, so don’t let me put you off entirely if they grow near you and you fancy giving them a try.

We are generally spoiled for choice for delicious conifers, so, while cypresses aren’t known to be worryingly toxic, I recommend avoiding them, at least initially, and focussing your explorations on the 4 families of easily recognised and super-rewarding needled conifers described below.

General Safety when Eating Conifers

Beyond the advice i’ve given earlier around avoiding yew and being a bit more wary with cypress species, here are a few extra considerations around eating the “edible” conifers. As so often when trying a new food, go easy first time around to ensure you aren’t individually sensitive to a species. Allergic reactions to conifers, while not common, are more likely than in more widely eaten food plant groups. It may help to think of conifers as a flavouring rather than nourishment (though they are high in some vitamins), and their strong flavours should in themselves help guard against over-consumption. Pregnant women should be extra careful, and many sources recommend against consuming any conifers during pregnancy. Many conifers are toxic to ruminants.

The Flavour Chemistry of Conifers

The key to understanding the remarkable flavours of conifers (and many other plants and trees for that matter) is a class of compounds called terpenes. These are a class of hydrocarbon with a very wide range of structures, properties and functions. Of the 100,000 or so chemical compounds that are known to play defensive roles in plants across the world, about 25,000 are terpenes. They are particularly prevalent in conifers, where they play an important role as a chemical defence against infections – especially by insects and fungi. Learn more about their role and function here. There is also evidence to suggest that they may play a role in communication between trees – see here.

No wonder that they are sources of rich and complex flavours!

For our purposes here, there are two key compounds that contribute most to the flavour profile of conifers.

Pinene

As its name infers, pinene has distinctive aromas of pine and fir. α-pinene is the most widely encountered terpenoid in nature. Pinene is found in many other conifers, as well as in non-coniferous plants, notably citrus fruits. It tends to react with other chemicals, forming a variety of other terpenes (like limonene) and other compounds.

Pinene is used in medicine as an anti-inflammatory, expectorant, bronchodilator and local antiseptic. α-pinene is a natural compound isolated from pine needle oil which has shown anti-cancer activity and has been used as an anti-cancer agent in Traditional Chinese Medicine for many years.

Limonene

Limonene is one of two major compounds formed from pinene. As the name suggests, it has a strong citrusy smells like oranges, lemons and limes – not surprising as it is a major constituent of citrus fruit rinds. It also occurs in the mint family.

Its plays an important role suppressing the growth of many species of fungi and bacteria and as a natural insecticide to ward off predators. Its fresh, delightful aromatics have somewhat backfired as it became a go-to constant of toilet cleaners (and those awful automated air fresheners that choke us at every turn). Limonene has very low toxicity and adverse effects are rarely associated with it.

Edible Parts of Conifers

Needles

The needles of many conifer species are rich in flavour and vitamin C all year round, but their tender young growth in spring tend to pack most punch. The earliest growth (usually April to June in the UK) of most species can be soft enough to eat in salads. Spruce tips are particularly tender. As they mature they darken and get too tough for pleasurable nibbling, but many still have great aromatics when you rub them vigorously in your hands, and are still great for infusing into hot water (tea), alcohol (especially mead, vermouth and gin), syrups, vinegars or blitzed and infused directly into granulated sugar or added to cake and shortbread mixes. See species notes below for the most rewarding needles to play with.

Rubbing the needles vigorously between my palms then smelling the result is how I go about getting intimate with a conifer that i’m meeting for the first time. I suppose this ritual is somewhere between a handshake and the way dogs sniff one another’s bits – a greeting and instant olifactory exploration of the tree’s character. As well as smell being an invaluable identification feature, this also allows me to assess what sort of condition an individual tree is in. On top of all of that, its just a fabulous way to deepen my connection with and experience of, a forest.

The benefits to human health of inhaling the compounds emitted by conifers (those terpenes again!) is well documented and one of the actions that underpins the idea of forest bathing. Read more about the science behind forest bathing here.

Two types of fir needles

Needles are best harvested by pruning off the ends of twigs or branches. Once home you can strip the needles from the twigs for using in recipes, though I sometimes include the whole twigs, mostly because i’m lazy, and partly because the woody parts can add an extra “woodsy”, tannic quality to infusions. Don’t leave needles hanging about – they are best used on the day you harvest them as their zinging aromatics can fade surprisingly quickly.

Resin

Resin often gets mistakenly confused with sap. Sap is the slightly sweet water that rises in trees in early spring – most often tapped from sugar maple, but also other acers and birch, then reduced to a rich, sugary syrup, fermented into wine, or just drunk as a refreshing spring tonic. Sap can’t generally be tapped in any useful quantity from conifers – at least not in the UK. Resin is the super-sticky fluid that drips from wounds and soon sets hard – the tree’s first aid kit, evolved to both trap and deter insect pests, repel fungal pathogens and seal wounds. It can be useful for human first aid in survival situations too, as an antiseptic dressing or soothing gargle for sore throats.

Pine resin on a damaged tree, starting to set. Fossilised resin becomes the precious stone amber. Source Wiki Commons

The antiseptic properties of conifer resin is largely due to its richness in terpenes. The concentration of these make it phenomenally flavoursome but not particularly good for you in quantity. (Two isomers of pinene constitute the main component of wood turpentine, which is distilled from the resin and used as a solvent). Overdoing it isn’t really very likely as conifer resin is incredibly strong in flavour and you’ll only ever need the tiniest whisper of it in food and drinks.

While exploring in Alaska I adopted the first nations’ use of solidified pine resin as a sort of chewing gum. Its pretty pungent and takes a bit of getting used to, but certainly keeps your breath fresh!

Noble fir – resin blisters and parallel silver lines on the underside of needles

A very small amount of resin can elevate conifer recipes to dizzy heights, but overdo it and it might taste like toilet cleaner! Resin can be harvested either by breaking pieces of set resin from the damaged bark, by gathering the dripping resin from fresh wounds, or (most fun of all!) by popping bark blisters containing liquid resin. These blisters aren’t present on all conifers, being most apparent on young to middle aged fir species.

Squeeze those plukes!

Squeezing “tree spots” is very satisfying and a lot of fun, but a couple of words of warning: the resin is extremely sticky, and will leave you pretty glued up if you aren’t careful (our 10 year undefeated tug-o-war team used it on our hands to help grip the rope!). I have also seen popped blisters shoot their resin direct into people’s eyes – not a pleasant experience!

You can see me making a direct hit on a camera in the opening sequence of this video. Keep watching and you’ll also hear chef and wild flavour boffin Craig Grozier expiate on some of the chemicals in conifers.

The best way to harvest sticky, runny resin for use in the kitchen is to squeeze the blisters into beech or sorrel leaves, then fold them up and put them in your basket. Resinous leaves can then be added one at a time to recipes, like this one.

Squeeze resin onto edible leaves like beech or sorrel for easy collection and transportation, then just add the leaf to your mixing glass

Alternatively, squeeze a tiny drop onto the lip of a water bottle then shake for instant conifer-infused water. I like to embellish this water with dandelion, tansy and birch bitters, balance it with syrup, then carbonate to make home made foraged tonic water. See my articles on rapid infusion and on instant foraged tonic for how to do this.

Gin and home made conifer tonic

Cones

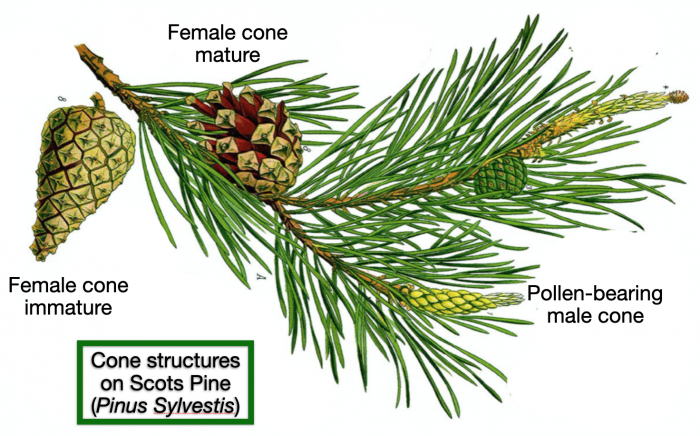

Conifers, unlike Broadleaf trees, do not have flowers or fruit. They have male and female cones. The botanical name for a cone is a strobilus. Pollen cones, like male flowers, release pollen and seed cones, like female flowers, receive pollen and develop seeds.

Male and Female Cones on Scots Pine. Adapted by Galloway Wild Foods from Wiki Commons.

Male Cones

The early pollen-bearing male cones of conifers, can be full of flavour. These are distinct from the female seed-bearing cones which develop later (discussed below), which are what most people think of as a “pine cone”. Early male cones are perfect for simple infusions into oils and vinegars – pick and crush them to check their flavour profile first. Infuse by simply immersing them in cold, lightly flavoured oil, vinegar or neutral alcohol (vodka) and leaving for a couple of weeks.

See my notes on larch roses below for more ideas.

Conifer Pollen

Male cones (sometimes referred to as “catkins”) can produce an abundance of sweet pollen in the spring which can be harvested by placing a bag over them and shaking. The flavour of the pollen is mild but it is high in protein and is very good for balancing androgen/estrogen levels, thereby boosting testosterone production. This can help promote stamina and sex drive. It is nice for dusting cakes with, or keep a jar of it in your pocket (or by the bed!) for when you need a bit of extra oomph! 😉

Pine pollen, May

Female Cones and Seeds

Seed-bearing (female) cones tend to me more substantial than male cones. When young and green they can be macerated with sugar to make mugolio, a richly flavoured syrup that is great for pouring on pancakes, mixing in cocktails and otherwise infusing rich, sweet conifer flavours into food and drink. There are detailed instructions on how to make and use it on the excellent Forager/Chef website here.

Most seed-bearing cones quickly become woody and loose flavour, but they make great tinder at this stage. Before you burn them or use them as decorations, its worth exploring them for their small, nutritious seeds. Squirrels tend to get first dibs on these, and in boreal pine forests its not unusual to stumble on large caches of pine seeds they have set by for winter. While exploring in the Yukon I found so many of these that it would have been possible to eek out an existence pilfering squirrel stashes alone. Given that a squirrel requires somewhere in the ballpark of 30,000 cones in order to make it through a sub arctic winter, that does seem a bit rude! Apparently squirrels pilfer one another’s larders as a matter of course and some may even specialise in theft rather than collecting their own. The white spruces (Picea glauca) that dominate vast areas of boreal N America have “mast years” every two to six years, when they produce an extraordinary hyper-abundance of cones. It is thought that this strategy has evolved to take advantage of the squirrel’s hoarding tendencies and absent-mindedness – ensuring that there is a large quantity of carelessly stashed or surplus seeds buried insures against harder times for the tree – especially in the event of a forest fire.

These are small morsels, but the large tasty pine nuts we pay top dollar for come from the pinyon (or piñon) pine group (especially Pinus edulis) that grows in southwestern North America.

The biggest conifer seed prize in the UK comes from mature monkey puzzle trees (Araucaria araucana), which seems only fair as their enormous needles (which are actually more like dragon scales) are almost impossible to work with. Their huge cones contain good sized seeds that are like large pine nuts, and can be used in similar ways. Don’t expect to find them on any monkey puzzle though – female trees don’t produce cones until they are 40 years old and need to be pollinated by a nearby male tree.

The giant female cones of a mature monkey puzzle tree. You really don’t want one of these dropping on your head! (Source Wiki Commons)

Conifer Bark

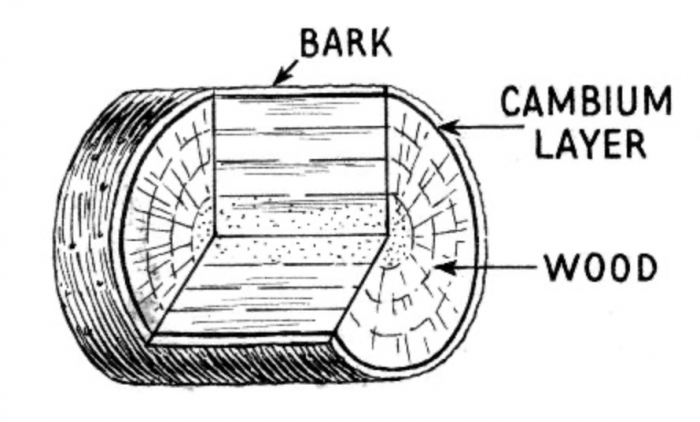

The soft, moist, white inner bark (cambium) of several conifers is edible and high in vitamins A and C. It can be peeled and chopped then eaten raw or fried like crisps, or dried and ground up into a powder for use as a flour for making flatbreads. This technique is most commonly encountered in Nordic and Sami food cultures. Read more about making pine (and birch bark) flour and bread here.

Cambium layer is just below the outer bark. Image: Wiki Commons

Though it is possible to remove just small panels of cambium from healthy trees, it is a serious and possibly life-threatening imposition, and only recommended in survival situations, or if the tree is being felled for other purposes anyway.

Sustainable and Considerate Harvesting From Conifers

Conifers tend to be big, hardy trees, and mature specimens will barely blink at you harvesting the tiny proportion of their needles, pollen, shoots or resin that are in reach. Harvesting cambium is a different matter and is discussed above.

Nevertheless, please remain a considerate forager, moving and rotating your harvesting areas. Most of the conifers encountered in the UK are likely to be deliberately planted monocultures. As plantations are a commercial crop, technically/legally you should seek the landowner’s permission before harvesting, even for personal consumption. In reality, the nano-proportions of the overall biomass that you are harvesting is likely to be so insignificant that this is probably a situation in which you’d be better off seeking forgiveness than asking permission.

If it helps your conscience, maybe see it as a tiny recompense for the vast industrial monocultures that commercial forestry imposes upon us. By using its flavours as a local, low-impact alternative to citrus fruits, you can feel pretty good about your food choices!

Juniper – Juniperus communis

Juniper growing prostrately on the exposed coast of Mull. Image ©GallowayWIldFoods.com

The most important of all conifers is of course juniper, without which we’d have no gin! The part most often used in gin is the immature male cones (which look like green berries) – almost always dried, and requiring only small amounts for a lot of flavour. Interestingly, the wood of juniper burns with hardly any smoke, making it the fuel of choice for illicit distilling (often in juniper-rich hills, away from prying eyes) in times of yore.

The female cones take between 8 and 10 months to mature (or longer in other species of juniper), whereupon they turn purply-black. It is the mature female cones that are predominantly used in food – classically with venison.

Female cones of juniper take up to a year to reach maturity. The green ones in the foreground are immature.

Juniper has two growth form in the UK. In exposed locations it grows flat and creepingly, while in more sheltered locations it grows more upright and can form and important part of the understory of upland Scottish forests. The foliage of juniper is aromatic, and I have successfully infused it into spirits and syrups.

I gather most of the juniper I use when visiting relatives in Canada. It is prolific in the wild expanses of Yukon Territory. ©GallowayWildFoods.com

Despite all the crowing about “locally foraged” botanicals, to my knowledge, only two out of our hundreds of UK gins actually use UK juniper – most is imported from the Mediterranean.

There are good reasons for this – juniper is very slow growing and under considerable pressure from upland grazing (pesky sheep and deer!) and the fungal pathogen Phytophthora austrocedrae. I’ve been trying for years to convince the gin brands that I work with to explore more abundant sources of similar flavours in alternative conifers. There are many nuances and variations on juniper’s aromatic, spicy-fresh aromatics in its more abundant evergreen cousins.

Connecting with juniper on the sea cliffs of Islay. A typically precipitous location for much of the UK’s wild juniper. This is partly due to the hardiness of the plant, but also because these are the only locations where it is relatively safe from sheep and deer grazing. Image ©GallowayWildFoods.com

For these reasons, while I recognise the unique and rarified aromatic complexity that juniper berries have, I can’t recommend harvesting more than a smidgen in the UK for personal use, and even then only if you live in one of its heartlands – mostly the highlands of Scotland.

Prostrate juniper near the summit of Foinaven, Sutherland, July.

A less troublesome way to forage for juniper is to spot its cousin Juniperus procumbens, or “garden juniper”, which is a very popular ornamental plant in rockeries. Befriend a gardener and i’m sure they would happily let you prune it back for them! It doesn’t have exactly the same profile as Juniper communis, but isn’t far off it. Take care as it can be quite prickly and can give you a skin rash – see my discussion of cypresses above.

Garden juniper – Juniperus procumbens. Source Wiki Commons.

Learn more about wild UK juniper with Plantlife.com – you can even adopt a juniper!

Recommended Conifers for Food and Drink

Provided you follow my guidelines on yew, and to a lesser degree, cypress, you really don’t need to accurately identify every conifer you want to play with. Connect with them by rubbing the needles vigorously between the palms of your hands and smelling. You’ll be amazed by the variety of distinct citrussy flavours they give off, from tangerine to lime to grapefruit, which can also help with identification.

When you find one you like, it’s nice to put a name to it, so below is a brief guide to identifying key families, with my thoughts on the most rewarding species for UK foragers.

Pine (Pinus spp)

Needles grow in clusters of 2, 3 or 5 which are “bundled” at the base.

There are over 100 species of pine in the world. Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris) is the most common pine in the UK – Harvest the young pine needles in spring, or better still the young pollen generating cones, which are full of flavour between March and May.

I favour early pine cones over needles for flavour

My Polish friend Szymon makes a tasty cough medicine-come syrup from the needle buds and early cones, which have a long history of medicinal use for bronchial complaints, especially in Eastern Europe. Once the syrup is strained off, Szymon partially dehydrates the sugar covered male cones to make phenomenal sticky pine sweets. Szymon is a font of great knowledge on all manner of Polish preserving techniques, which he shares generously on his website and social media feeds.

Unlike other conifers described here, pine needles tend to toughen significantly as they mature and don’t give up much flavour after spring. Pounding, chopping and whizzing in a food processor can help flavours more readily infuse, but generally I just turn to other conifers that are more keen to give up their flavours as the year progresses (mostly fir and spruce). Having said that, some varieties of white and black pine can be extremely aromatic all year round, though hard to come by in the UK. Try pounding them with sugar and/or infusing into simple syrups and vinegars.

Szymon Szyszczakiewicz with his delicious pine-bud sweeties

Spruce (Picea spp)

Stiff, sharp needles are square or triangular in cross-section and grow individually, all around twigs and branches. When detached, the needles will leave a rough, woody projection on the branch. The easiest way to identify spruce is to try to pick some – if its really hard to do without pricking your hand, you probably have a type of spruce!

Young spruce tips, about to shed their papery sheath, April

Spruce tips picked in the spring are soft and much brighter green, emerging from rust coloured, papery parcels and exploding with lemony freshness – one of the greatest gifts of spring. They make great syrups, cordials, sorbets and ice creams. Blitzed with sorrel and apples then strained, they make a great cocktail ingredient – perfect instead of lime juice in daiquiris.

‘Amuse Bush” – Magnolia and spruce tip sushi

Sitka spruce (Picea sitchensis) are extremely common in the UK – it is this conifer that makes up most of our large monoculture plantations. Norway spruce (Picea abies) is also quite common. You’ll know you have a spruce tree pretty quickly, as the twigs are seriously jaggy, especially when you rub them in your palms to awaken their aroma. But its well worth doing – the mature needles have a rich complex flavour, with more bass-notes than many of their coniferous cousins, great for infusing into mead or with bitters in foraged vermouth.

Spruce tips at their perfect size-flavour-tenderness ratio

Fir (Abies spp)

Flexible, flat needles grow individually from twigs and branches. Although (on very close inspection) they emerge from all around their twig, they are usually twist themselves as they grow on to a more-or-less flat plane. Look for 2 parallel silver lines on the underside of each needle – if these are not present, make sure you aren’t looking at yew, the needles of which also grow on a more-or-less flat plane. The female cones of fir trees grow pointing upwards which differentiates them from many other conifer families.

Noble fir needles and male cones add a pine-meets-grapefruit flavour

Fir is my favourite conifer family for flavours that work well with gin, especially Noble Fir (Abies procera) and Douglas Fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii – not a ‘fir’ in a strict scientific sense, but near enough). I’m delighted to say that noble fir made it into our very good local Galloway gin – Hills and Harbour – after I introduced it to the guys in their early recipe development stages.

Fir makes a great flavouring for bread. My friend Craig Grozier makes a deeply delicious fircaccia bread, substituting rosemary for douglas fir needles, which he also blends through the dough.

All set up for a wild cookery session on Islay, with Craig’s superb fircaccia bread in the foreground

Fir needles are also good for using in meat marinades, or for adding to roasts and roast potatoes as you might rosemary. Also try stuffing the twigs into the belly cavity of whole fish (especially mackerel) before baking. The citrussy aromatics will add their flavour as it bakes.

Marinading Roe deer haunch with pontack (spiced elderberry vinegar)and doulas fir

The needles of most firs provide fantastic grapefruit – tangerine flavours at all stages of growth, though spring growth is vibrant. Its my go-to cocktail conifer and makes fabulous syrups, shrubs, meads and direct infusions into gin.

Douglas fir needles – note the two parallel silver lines on the underside of the needles(R)

Larch (Larix spp)

Larch is easily identified by clusters of narrow needles growing from woody nubs, larch is one of very few conifer varieties that go brown in autumn and shed their needles over winter.

Harvest the young needles in spring and early summer, when they are bright, near luminous, green and have a sharp, sorrel-like flavour. In the spring you will also find very cute wee cones that look like exotic fruits. These have decent flavour and are much esteemed for pickling or fermenting by chefs. Personally, cute as they are, I find more flavour in the young needles, from which I make gallons of cordial every April.

To make some yourself, follow my nettle cordial recipe, substituting in the young needles.

Young larch needles (April) and male cones – often referred to as “larch roses”

Most larch trees you encounter in plantations will be European larch (Larix decidua), which has been suffering from an epidemic of its own and social distancing of them (by cutting down huge swathes) has been going on across much of the UK. Larch disease is a fungal infection (Phytophthora ramorum), and is causing the demise of large swathes, mostly in the damper West – Galloway is the worst hit. The pathogen can also spread to sweet chestnut, spruce, fir, blueberry (blaeberries in Scotland), and more. To minimise the risk of you inadvertently becoming a vector of transmission you should avoid harvesting from sick trees. Signs of larch disease include:

- Blackening along base & midrib of the leaf

- Withered and blackened leaves or needles leading to dieback of the outer branches.

- Areas of black “bleeding” on the trunk

Check for these signs before harvesting, and if you see them, its worth reporting to Tree Alert

In parks and cities you may also encounter ornamental larch varieties, especially Japanese larch (Larix kaempferi) with attractive blue-green needles and downswept branches.

The Firgroni: Equal parts, fir-infused gin, sweet vermouth and my ‘Campartree’ fir-larch-tansy bitters

Drink Your Christmas Tree

Its quite likely that your christmas tree will be a spruce, fir or pine, and so long as it hasn’t been sprayed with needle glue or fire-retardent (check with the retailer), there is no reason that you can’t make it into a delicious christmas cocktail.

The Noble

Don’t wait until you are throwing it out after christmas though – it will be dried up and flavourless, even if it still smells piney. Rather, use those bits that you trim off during the ritual struggle to make it look perfect.

Needles infused in gin will have imparted much of their flavour in a few days, so a tree erected in advent can be part of your christmas morning tipple.

Make mine a Noble Martini!

More Forager’s Guides:

7 Comments

Thankyou for this fascinating read. So much useful information and the best conifer ID guide I’ve come across. Really looking forward to trying this new foraging source for me in the spring. The time you put into these free guides is so appreciated.

Thank you so much for this fascinating and generous article. Really beautiful. I wanted to make something with those beguiling larch roses. And now I know to make the larch cordial. Wonderful.

As a completely side issue. Do you think any pine/conifer would go with cheese?

Hi there what veggies and edibles would mix well around conifers? Thanks for tips..

wasn’t clear on this section:

“Yew needles are probably most similar to the shortish needles of Western Hemlock (Tsuga heterophylla), so be extra extra careful to observe their silver tramlines and citrussy aroma if you are harvesting from them.”

Harvesting what exactly?

If you are harvesting western hemlock needles, be sure to observe those characteristics, so as to be sure you don’t have yew! Mark

This excellent site will go a long way in my knowledge of evergreen foraging. I have been drinking and bathing in cedar tea since a child, and in the last few years, using spruce buds, and juniper berries.

Looking forward to expanding my foraging.

Thanks.

This is great. Does Juniperus procumbens have more flavourful needles than Juniper communis. Do Juniper communis needles have a flavour that can be used too?