Foraging Starts at Home

It can be tempting for novice foragers to spend a lot of time looking for things.

This is entirely understandable – “foraging ” certainly implies a degree of searching and some wild plants can take a good bit of finding. But it is much more efficient and rewarding to learn to recognise resources that are hidden in plain sight close to home.

Pineapple weed – a great example of a delicious “weed” that hides in plain site in both urban and rural settings

95% of an experienced forager’s repertoire is likely to consist of common weeds. Hardly any of the wild plants mentioned on this website are in any way rare. In fact most could be described as hyper-abundant, several as problematic “weeds”. Within their distribution range, lots of good things don’t take a lot of finding. The real challenge is in drawing back the green veil of a hedgerow, wood or field, identifying its useful parts, and knowing how to considerately harvest and use them.

The notion that forager’s are travelling around the country harvesting rare species to extinction is the most common misunderstanding of what foraging is. Most foraging is in fact a thinning of abundance. You can read an in depth exploration of this here: Foraging in the Modern World: Protecting Rare Species

That foraging starts at home is not always an easy lesson to learn, and although I advocate it regularly on my guided walks and events, I have to constantly re-learn it. Let me give you an example…

There is a charming little plant called sweet woodruff that is beloved of foraging chefs and creative bartenders for its sweet vanilla-meets-hay scent that infuses remarkably well into syrups and spirits – who needs tonka beans? In my excitable early foraging years I was eager to explore its delights (it makes a mean zubrowka), and kept what I thought was a keen eye out for it in my travels around the UK.

Sweet woodruff

After a year or so with it high up my “must find list”, I was delighted to discover it in a woodland edge in NE Scotland – about 5 hours drive from my home. No matter – I was delighted to have finally run down my quarry, and it barely mattered that I might only be able to harvest it once a year.

About a year later while exploring a large woodland about 50 miles from home I found it again. Rejoice – I’ll be by a few times a year to harvest.

6 months later, and I pull into a layby about 10 minutes drive from home that I’ve stopped in a hundred times before. This time I happen to need a pee and pop through the hedge for some privacy… Lo and behold! Sweet woodruff! (I didn’t pee on it!) How had I overlooked it for all these years?

Several years after my first momentous discovery all those miles away, I take a wander up the lane by my garden, squeeze through a hole in the wall and down to the riverbank. And there, bold as brass, basking less than 3 minutes walk from my kitchen is a swarm of sweet woodruff…

This experience, and several others just like it, encouraged me to take a much greater interest in the close environs of my house – to search less and learn more.

Late summer selection from the Fleet Valley where I live

I estimate that, over the course of a year, I can harvest 200 different wild ingredients within 15 minutes walk of my kitchen. On a bike, I can reach the coast in the same timescale, increasing the list to about 350.

I’m fortunate to live in a rural valley with a rich and varied landscape. But a similar experiment in the west end of Glasgow unlocked over 100 tasty, nutritious wild plants.

Nothing has shone a light on this abundance and variety more brightly than Corona virus. The first lockdown in the UK (March – May) coincided with the spring surge of greenery, and stressed, confined people everywhere took the opportunity to delve more deeply into their gardens and local green spaces. Amid all the challenges of lockdown, the slowing down and focus on local outdoor activity brought the benefits of foraging into sharp focus: foraging gently exercises the body while demanding just enough thought and focus to take our minds out of the day-to-day. It is a practical exercise in mindfulness and meditation for those that may not otherwise be drawn to deep introspection. It is learning by doing, connecting through intimacy.

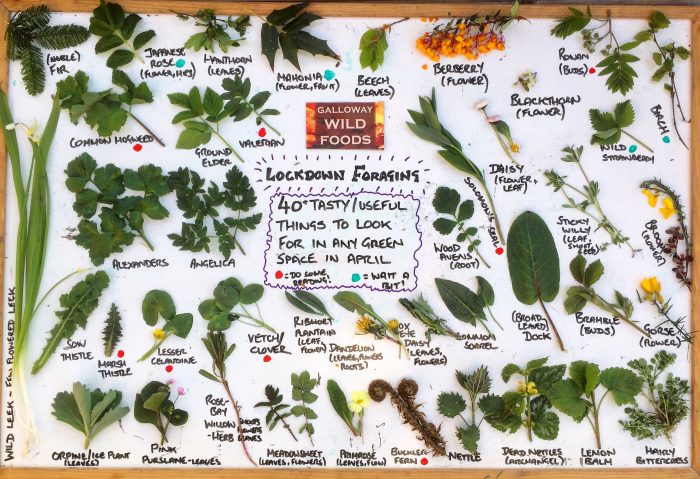

Lockdown Foraging – 40 or so useful, accessible wild/feral plants

This quote that was posted on my Facebook Page sums up the sense of belonging and connection that foraging can bring, as well as its benefits for mental health:

“As a technical ‘foriegner’ (moved to England when 4 and never applied for British passport as have an Irish one) I had always felt disconnected from Britain. This in part led to mental health problems.

Foraging has been immeasurably beneficial for me. Firstly to reconnect with myself and nature. But also to gain a real sense of belonging to the beautiful and bountiful land, and a passion to help regenerate it.

I feel foraging is one of the best medicines out there”.

I encounter similar experiences regularly, especially from many of the foragers i’ve been working with on a regular basis through my online wild food mentoring scheme.

My first advice to any aspiring forager is to start at home. Fathom out flower beds, research riverbanks and unpick your park. Challenge yourself to make a meal or drink just from what you find there. You will be pleasantly surprised and almost certainly driven to new levels of creativity.

Slow down – learn your land

Related Posts:

- Foraging During the Coronavirus Pandemic

- Foraging in the Modern World – A series of blogs exploring the politics of foraging

- Foraging during the Coronavirus Pandemic

- Where The Wild Things Are

- Wild Creeping Time – An exploration of place, time and nature connection during lockdown by author Sarah Thomas

_____________________________________________________

View this post on Instagram

A version of this post originally appeared on The Botanist Gin website