Wild Garlic/Ramsons – Edibility, Identification, Distribution, Ecology, Recipes

Allium ursinum

AKA Ramsons, Buckrams, Broad-Leaved Garlic, Wood Garlic, Bear Leek, or Bear’s Garlic

Edibility – 4/5

Tasting strongly of spring onions and garlic. All of the plant is edible, including shoots, leaves, buds, flowers, flowering stems bulbils, seeds and bulbs/roots, though the latter should not be dug up as they tend to lack flavour/texture and you will be undermining future populations.

Wild Garlic – Identification – 3/5

Leaves are lanceolate (a narrow oval shape tapering to a point at each end), 10-30cm long by 3-6cm wide at their widest point when fully grown, hairless, vibrantly green in colour and smelling of garlic and onion when crushed, damaged or decomposing. Growing from small bulbs with fine roots (like spring onions/scallions).

Flowers are small, white, 6 petalled, with around 25 arranged in a “starburst” or “pom-pom”-like globe when fully open, held higher than the leaves on a leafless stalks that are triangular in cross section.

Seeds casing are born on the pom-pom, initially green 2-3mm at the edible stage, turning black and hard with age.

Wild Garlic – Lookalikes

Related UK species include few-flowered leek (allium paradoxum) and three-cornered leek (allium triquertum) both of which have narrower leaves. Both are good to eat but lack the flavour of garlic, tasting more like intense spring onions (aka scallions). You should also be aware of lords & ladies (arum maculatum) and lilly of the valley (convallaria majalis) – the former being very astringent in the mouth, so unlikely to be consumed in any quantity. Lilly of the valley contains nearly 40 cardiac glycosides and is potentially deadly. Dog mercury (Mercurialis perennis) looks nothing like wild garlic, but it often lurks among it to catch out careless harvesters. Read more about them below. Wild garlic (Allium ursinum) appears not to be found in North America, but ramps (Allium tricoccum) are common in many areas of Eastern N America.

Ramsons v Ramps – What’s the difference?

There seems to be some confusion in foraging literature over the difference between ramsons (wild garlic, A.ursinum) and ramps. For clarity, ramps (Allium tricoccum – also known as wood leek or occasionally, and somewhat confusingly, wild garlic) is found wild only in Eastern North America. Another Eastern North American species Allium burdickii is also sometimes loosely referred to as ramps. I have never foraged or eaten ramps, but from what I read, they are very similar to their European relatives in look, habitat, flavour and usage, though there does seem to be more of a tendency to uproot them in the US. The best exploration I’ve found of ramps and their harvesting in North America is here.

Wild Garlic – UK Distribution – 4/5. Abundant, often hyper-abundant, across most of the UK in appropriate habitats. Less common in Northern Scotland.

Habitat – Shady hedgerows and open, well established deciduous woodland, with a strong preference for damp ground. Woodland stream edges are good places to look.

Season – February – June – Wild garlic completes most of its life cycle before woodland canopies are in full leaf, thereby taking advantage of daylight and the rich humus of rotting leaves from previous years. I know a spot near the coast in Galloway, SW Scotland where the first shoots can be seen (if you know what you are looking for!) around christmas, but this is about as early as you would see them in the UK. More typically, shoots become obvious in early February, though it may be a month later than this in northern/inland/upland areas.

Wild Garlic Ecology

Wild garlic is a bulbous perennial that reproduces through bulbs and seeds. It can take as much as 4 years for plants to reach reproductive maturity. Vegetative self-propagation can be responsible for as much as 50% of its reproduction, though reproductive strategies appear to vary significantly between localised populations. It is used as an ancient woodland indicator species (which is not to say that its presence alone indicates that a woodland is ancient). Each plant has both male and female organs. The flowers are pollinated by bees, moths, hoverflies, beetles and other flying insects. Wild garlic is the primary larval host plant for a specialised hoverfly, ramsons hoverfly (Portevinia maculata), which tunnel through and overwinter in the bulbs.

Wild Garlic – Sustainable Harvesting

Although wild garlic can seem endlessly abundant where it is well established, don’t forget that other species have evolved to rely on that abundance. Although wild garlic will grow back the year after being cut, repeated cutting year-on-year will weaken and eventually reduce once dense colonies. Here are some thoughts on how to be a sensitive wild garlic harvester:

- Spend time getting to know your local patch, and spread your picking around different locations within a season, and from year-to-year, never stripping large areas, but thinning abundance.

- Resist the temptation to grasp a whole clump and hack it off at the base, instead hand-picking a few leaves from each clump, or cutting a section of a clump.

- Gather from the middle rather than the edges of colonies.

- Consider that other foragers may be visiting too, and try to develop a sensitivity for which locations are being hit hard.

- Don’t uproot them for food – the bulb isn’t great eating anyway. (In the US, the closely related ramps (Allium tricoccum is more often uprooted – for an excellent in-depth exploration of harvesting ramps (which is also of some interest to UK wild garlic harvesters, see here).

- Give something back, and promote new colonies, by dividing a few plants (bulbs intact) from thriving colonies and introducing them to other suitable habitats.

- If you are gathering the green seed pods, leave plenty to mature on the plant and return when they are black and ready to fall to spread some further afield (they aren’t reproductively viable at the green stage).

If you think wild garlic might be on the retreat in your locale, consider seeking out wild leeks instead. Few-flowered leek and three-cornered leek are both problematic non-native invasives in the UK, so you needn’t worry about taking too many, provided you don’t introduce them to new locations.

Related pages:

- Know Your Onions – An Introduction to the Allium/Onion Family for Foragers

- Wild Leeks – Edibility, Identification, Distribution, Ecology, Recipes

Wild garlic has been at the forefront of the renaissance in wild foods in recent years. It isn’t hard to work out why: it is easy to find, delicious, and fairly straightforward to identify. This is an abundant plant in most areas of the UK, though I have heard the closely related ramps (allium tricoccum) are suffering in some areas of the US near to urban centres, where they are usually dug up. I’m not quite sure why this practice has become standard for harvesting ramps, it seems inconsiderate and pointless to do this with wild garlic, the bulb being a poor prize for the undermining of future populations. Even with the regular harvesting of just its arial parts takes its toll on perennials if done inconsiderately, year upon year. I expect populations near some urban areas in the UK may start to suffer as foraging continues to increase in popularity. I would urge anyone to pick considerately, not clearing large areas, but spreading their picking across wide areas (I call this thinning abundance), and increasing their repertoire of foraged edibles.

Its crowded ranks of sleek, lanceolate leaves can carpet large expanses of woodlands, filling them with nodding white starburst flowers and the smell of garlic. We have a small mountain in Galloway named Garlick Hill – unfortunately, now given over to plantation forest – which I assume must have been blanketed in it once.

As you might expect of the allium family (which includes onions, garlic, leeks etc), the flavour is a delightful combination of garlic and spring onions. Early shoots, like most wild greens, are the most pungent – though never too overpowering. The flavour of the leaves mellows and their texture coarsens as the season goes on and pass their best once they flower. The flowers are also edible, and make the finest natural garnish I could possibly imagine. If you pick them early in the season when they nestle in the young leaves they are elegant and delicate, still wrapped in their translucent sheathe and make tremendous pickles.

Garlic has famously been employed to deter vampires. As with many legends, this has a basis in more practical traditional uses as a blood purifier and the pungency of its active compounds to deter blood-suckers. The juice of most alliums can be useful in deterring biting insects. To be honest, I favour a midge net, and be warned, smearing yourself in wild garlic juice may see off more than just a few insects!

The flavour of alliums that we now hold in high esteem is actually a defence evolved to deter grazing. Unmolested pre-flowering alliums tend to be more or less odourless. The second they are cut, bitten or otherwise damaged, the enzyme alliinase converts alliin into allicin, which is responsible for the pungent garlic and onion flavours so appealing to most humans, but reprehensible to grazing animals (this is why wild garlic patches only really start to make the whole woods smell of garlic when they are well on in their growth cycle – essentially because they are starting to decompose). Allicin is actively toxic to many animals, reducing the bloods capability to carry oxygen. Don’t let your dog eat wild garlic.

This clever defensive strategy is a real own-goal when the onion family meets humans. As well as being delicious, allicin and other compounds found in alliums such as kaempferol and quercetin, have proven anti-bacterial, anti-fungal and anti-viral properties. They can be useful in the treatment of everything from bites, wounds and headaches, to heart diseases, cancer, viruses and lots more.

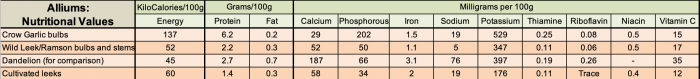

Nutritional values of a few alliums. Compiled by Galloway Wild Foods from multiple sources, notably Robert Shosteck “The Nutritional Value of Wild Foods” and Self Nutrtion Data, both online

In a bush-medicine context, you’d do well to consume plenty of raw allium greens and bulbs for their gentle, natural antibiotic and antiviral properties, as well as their all-round nutritional profile. Laying the bruised leaves or rubbing the juice of say, wild garlic, on cuts and sores can only help, perhaps in conjunction with ribwort plantain (plantago lanceolata).

The one part that isn’t worth eating is the bulbs. If you are hoping for something resembling cultivated garlic, you’ll be disappointed. They tend to be wet, slippery and lacking much of the appeal of the rest of the plant. Not generally worth the trouble, though on a few occasions when I have found them washed out by flooding in early spring, then dried a little through exposure, they have made good pickles – a la pickled onion.

Wild garlic bulbs – not recommended for digging up, but if they get washed out, seems a shame to let them perish…

Ramsons – to use their more poetic name – are versatile in the kitchen. Their pungency works well in a variation on pesto, and you can make it extra wild if you use pig nuts or hazelnuts. They are very happy in the company of goats cheese and I use a hard Galloway goats cheese instead of parmesan.

Recipe: Wild Garlic, hazelnut and goats cheese pesto

The broad leaves can be used to wrap and layer – I have successfully used it to make dolmades and sushi rolls. It is possible to make excellent sauces and soups, but the oils that give ramsons their allium flavour are highly volatile and soon lost during cooking. I have come across too many misguided chefs bragging about their use of wild garlic, who have cooked every last vestige of taste out of it. I do sometimes sweat the white stems as a background flavour, but always add the freshly shredded green leaves at the last second to retain their garlicky aromatics.

Delightful as ramsons are, the flavour can be a little one-dimensional. It is possible to elevate them (and other alliums, or most wild vegetables for that matter) to spectacular new levels by lacto-fermenting them. This may sound daunting, but is in fact one of the simplest and most rewarding preparations, and means you can enjoy an allium buzz all year round.

Recipe: Lacto-fermented Wild Garlic

I said ramsons are fairly straightforward to identify as there are a couple of potential traps waiting for foragers who get over-confident or slap-dash in their picking. The worst (and hopefully most unlikely) mistake would be to gather a couple of early basal leaves of foxglove while picking carelessly. It is not that the leaves are particularly similar (thick, hairy and serrated rather than thin, sleek and smooth), just that they can grow in amongst ramson patches where coarse foragers may be tempted to tear up indiscriminate armfuls.

Take care that a rogue foxglove leaf doesn’t sneak into your wild garlic harvest – the consequences could be fatal. You can see here that they are significantly different.

Much more similar are Lilly of the Valley, Autumn Crocus, daffodils, snowdrops and Lords and Ladies. All of these are toxic to humans – lilly of the valley is potentially fatal. None have the distinct scent of garlic, but as ramsons become the wild food of the masses, there will almost certainly be incidents in years to come.

Take care not to confuse young wild garlic shoots (below, pictured in mid January) with toxic snowdrop shoots (above), which have a bluish hue, and noticeable sheaths

Dog mercury, Mercurialis perennis. It looks quite unlike wild garlic, but often lurks among it to catch out foragers who harvest carelessly. It could make you quite ill, though is unlikely to be life-threatening unless consumed in significant quantities.

Related Pages:

- Know Your Onions: An Introduction to the Allium/Onion Family for Foragers

- Wild Leeks

- Edible Wild Plant Guide

- In Season Now

- Spring Foraging

- Wild Food Recipes

View this post on Instagram

View this post on Instagram

View this post on Instagram

6 Comments

Great article. one of my favourite wild foods. The flowers are a lovely addition to salads and the early leaves are available as early as janurary. A great addition to muscles and your spot on when you talk about adding them at the last minute. dont wanna miss out on the flavour. They also keep really well in the fridge. bang them in a ziplock fridge bag and they really do keep for weeks. nice one Mark!

This is interesting.

About this wild garlic, they have many different name.

I know there are huge popular in U.K. or Northern Europe & Russia.

But some people found them here in northern Michigan.

It is very impressed.

Thank you for nice photos.

I hope some companies sell this wild garlic pickling.

It is very healthy food.

Specially people who like red meat.

I have seen a couple of recipes for pickled buds from the wild garlic, does anyone know what you would serve them with?

Anything that is nice with a garlicy pickle… cheese? Salad? Side on a stir fry? Sushi?

I saw lily of the valley in a neighbours garden this week. The flowers were helpfully just coming out but the picking season for wild garlic has been going for ages during which time the lily of the valley would have had no flowers I was struck by how incredibly similar the leaves are. People say that lily of the valley grows from one stem whereas wild garlic grows on individual stems from the ground but I have seen two leaves of wild garlic and a bud growing from the same stem. How do you make sure you avoid lily of the valley?