How to make Vermouth and Amaro with Foraged Botanicals

I love making vermouth and amaro. They are where two great passions of my life overlap: foraging and drinking.

Vermouth and amaro making is up there with mead making as a deeply satisfying forager’s playground where the inspiration of wild flavours and enquiring palates come together in a straightforward process to make something uniquely tasty. They can be drunk straight or with soda, but are most often used to add rich sophistication to other drinks, especially in cocktails. Martinis, negronis, manhattans and myriad other classic cocktails rely on their bitter-sweet depth to make them sing.

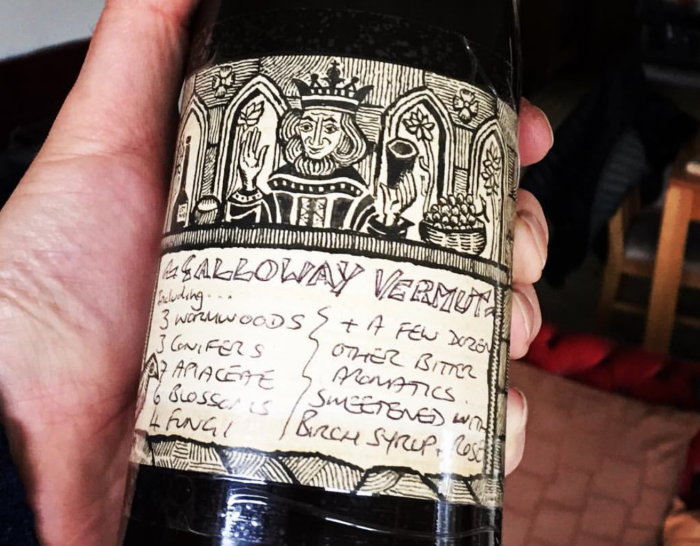

A range of foraged vermouths and amaro of different styles: Dry spring vermouth (dry, herbaceous), Sweet lockdown vermouth (fruity, sweet, floral), Wild Fungi Vermouth (Umami-mushroom), Camper-tree Fir-Larch-Tansy Amaro (Bitter-sweet & citrusy – without citrus!), Galloway Bog Fernet (funky deep aromatic bitters). ©GallowayWildFoods.com

Making vermouth is the ultimate expression of drunken botany, calling on ID skills, plant craft, imagination, techniques and taste. The balancing of bitter, sweet and aromatic flavours, allows you to connect with and use some plants that are generally considered too pungent or bitter for normal food and drinks uses. As you invest time in learning this craft, herbs that you once turned your nose up at will take on exciting new possibilities. That strange syrup or infusion at the back of your cupboard that didn’t quite make the grade at christmas can suddenly become the star of a gastronomic show.

Below is a deep dive into all things bitter aromatic and boozy, based on many years playing about with plants and cocktails, and learning from some amazing bartenders. Please don’t be daunted by its length – this could be the beginning of a beautiful friendship!

Related Pages:

- Wild Booze Recipes

- How to make mead easily using wild plants

- Brief instructions on making foraged amaro and shrubs

- Botanical Booze Foraging

Life is too short not to be bitter…

Most human palates have barely more than binary sensors for sweet and salt. They can identify perhaps a few types of sour, and maybe half a dozen strains of umami. But most humans can discern over 300 types of bitter flavours.

There are good evolutionary reasons for this: bitter is the flavour of many health-giving or medicinal plants (think of dandelions and brassicas), but also a large number of toxic plants and compounds (notably alkaloids and bitter almond flavours in the rosacea family – the flavour of cyanide).

Distinguishing between bitter flavours would have been literally a matter of life and death for our hunter-gatherer ancestors. For this reason not only our mouths, but our whole alimentary canal, stomach and gut, have evolved to interpret nuanced variations of bitterness. Guys – you even have bitter receptors in your gonads! I’m not quite sure why…

Rather interestingly (at least for flavour geeks) there is a genetic split in homo sapiens between bitter sensitive palates (sometimes referred to as ‘super tasters’, as such individuals also have more receptors for other flavours), and bitter tolerant palates. Why? Consider early humans, living in small groups and tribes, colonising new new parts of the world and encountering new flora that presented both new food opportunities (survival) and new dangers of poisoning (extinction). It paid for the gene pool to have both bitter tolerant “adventurous eaters” to open up new nutritional avenues, and bitter sensitive/averse “super tasters”, who were likely to play it safe. Neither tasting gene died out, as both were important to both the adaptability and safety of early human social groups.

So it may be worth considering that, when you won’t let your kids leave the table until they have eaten up all their sprouts, that they might be a super taster, and that what tastes like a pleasant sprout to you, may taste like a bitter-bomb to them!

Sensitivity to bitter takes lots of things off the menu, and if you have that gene, then you probably don’t enjoy the more intensely bitter end of the cocktail spectrum, and vermouth may not be for you. Having said that it is certainly possible to retrain palates. This is something we have done as a species as well as individually. Most modern vegetables have been selectively bred towards sweetness and away from bitterness, not always to the benefit of our health. Our addiction to sugars has made many people bitter-averse and skewed our collective tastes away from the joys of bitters.

The Bitter Potion, Adriaen Brouwer, 1640. The sitter had obviously just tasted a bitter medicine and his extremely distorted facial expression is evidence of deep disgust. Perhaps he was a “super taster”! Hopefully your foraged vermouth will produce a happier reaction!

Whether you are a super-taser, or have a mollycoddled palate, biology is not destiny and it is possible to recalibrate. By starting with gently bitter drinks, you can retrain yourself to enjoy the infinite nuances of bitter aromatics. Start light, and go with what is comfortable, and most importantly, enjoyable!

What is vermouth?

Regardless of genetics and sugar addiction, most humans still love bitter drinks. We chug gallons of tea and coffee every day, both of which are high in bitter compounds. Most cultures are also pretty fond of beer, which usually has a strong bitter profile. But after beer, the most widely drunk bitter liquid in the world of alcoholic drinks is vermouth.

Vermouth is an aromatised wine, traditionally made by infusing a base wine with bitter aromatic herbs and fortifying with further alcohol. Its genesis was as a medicinal “tonic wine”, high in bitter compounds (those useful ones I mentioned earlier) which would help to expel intestinal worms and address other medieval ailments. Foremost among the bitter herbs used was wormwood, the German for which, vermut, is the origin of vermouth. The only real “rules” governing what can and cannot be called vermouth in a commercial setting are that it comprise 75% base grape wine and some wormwood. The varieties most commonly used in commercial vermouths are absinthe wormwood (Artemesia absinthium) and roman wormwood (A.pontica), though there are many species across the world. Dolin, Noilly Pratt and Martini (the brand, not the cocktail) are some of the best known dry vermouths, and Dubonnet and Carpano Punt-e-Mes are well known examples of sweet vermouths. Tippling your way around a few of these classics will help you to get a feel for how you’d like your own vermouth to turn out!

I found this Eskimo wormwood, artemesia telesii, on a paddling trip on the Nisutlin River, Yukon, Canada. ©GallowayWildFoods.com

Italy has a deep passion for bitter aperativo, but often don’t use wormwood in their aromatised wines, favouring other potent bitter aromatics, especially gentian root. So although they work in similar ways, they aren’t sold as vermouth. If you want to go straight to the high end of Italian “vermouth style” drinks (very useful inspiration for your own concoctions), I recommend starting with Cocchi’s range.

Gentian is generally too rare in the UK to consider harvesting the root unless you are growing it yourself. But it was abundant on the limestone mountains of Canada so I gathered a handful – just a few of those tiny roots go a very long way! ©GallowayWildFoods.com

What is Amaro?

Italy is also famous for its boozier style of herbal liqueurs, known as amaro (plural amaros, or amari). Nearly all of these have a strong bitter profile, usually balanced with sweetness. The best known of these is Campari, which uses the bitter citrus of orange peel, but there are many more complex and nuanced variations and regional styles which defy categorisation. For a quick intro to their key features and styles, see here. If you are going to make your own, its helpful to first taste what the experts make. Assuming you are familiar with Campari and Aperol, I’d recommend trying Amaro Montenegro or Amaro Nonino as really good gateway amari. Remember that bitter is often an acquired taste, so if you jump right in to say, fernet style amaro, you may be overwhelmed!

Home made amaro can be made in similar ways to the vermouth process below, by omitting the base wine, and just blending your tinctures with your syrups. For example, I make my Scottish Campar-tree (see what i’ve done there? 😉 ) by blending noble fir tincture with larch cordial and a selection of other bitter tinctures.

Check out a brief amaro recipe here

I urge you not to take any rules too seriously when making your vermouth, amaro or bitter-sweet concoction. Regulations and terminology are usually set down to protect large producers and needn’t concern the nimble palates of home foragers, creative drinkers and drunken botanists. You can certainly make a tasty bitter-sweet aromatised wine at home that hasn’t been near any wormwood, and still call it vermouth. Think of it as shorthand.

Having said that, wormwood is pretty much my acme of bitter aromatic joy. Its aroma is more pungent than even the punchiest of mints (I get a head buzz just from smelling it) and even a tiny nibble is likely to have even the most committed of bitter afficianados wishing they hadn’t. A little goes a long way.

Wormwood is predominantly Mediterranean in its European distribution, but is not uncommon in the South of England, mostly near the coast.

Artemisia pontica, Roman Wormwood, not uncommon in the wild, near the coast, in S England. Source: Wiki Commons

I am yet to find absinthe or roman wormwood growing wild in Scotland (though they are easily grown in herb gardens), but I am lucky enough to be acquainted with a few large colonies of sea wormwood (Artemesia maritima), which also goes by the intriguing name of Old Woman. Much more common is its near relation mugwort (Artemesia vulgaris) a delightful herb that shares many of the aromatics of true wormwood, but little of its bitterness.

Sea Wormwood, Artemesia marítima, grows wild around Scotland. It is so pungent that only small quantities are required. ©GallowayWildFoods.com

Wherever I travel, I try to seek out the aromatics of that place and make a vermouth to capture its essence.

Yukon Vermouth: Made with fringed wormwood, gentian root, eskimo mugwort, creeping juniper, subalpine fir, N American hogweed (heracleum maximum) seeds, thyme, yarrow and birch syrup

Wormwood aside, there are dozens, possibly hundreds, of super-common and easily identified wild plants with which you can make your own vermouth. Making the vermouth of a place is a lot of fun – capturing the taste of a place in a liquid.

Wild lands with poor soils tend to have an abundance of exciting bitter aromatics – I was spoiled for choice in the Yukon, and a local supply of birch syrup made the perfect sweetener.

How to make Foraged Vermouth

Making your own vermouth is easy, but requires a bit of plant knowledge and some forward planning. Here is the basic process that works for me, in headline form first, then in more detail:

- Select the plant (or fungi or seaweed) that you wish to use and assemble “interesting potions”:

- Make tinctures from some of your chosen botanicals

- Make syrups from some of your chosen botanicals

- Select a base medium (usually wine)

- Infuse some botanicals directly into base medium

- Fortify with tinctures

- Sweeten with syrups

- Clarify and bottle

If you need advice and support on your vermouth-making journey (or anything else foraging related) i’m just a few clicks away – book your online 1-to-1 mentoring/tutorial here!

________________________________________________

1. Select the plants that you wish to use

Any plant you like the smell/taste of is fair game. Obviously you should ensure that it isn’t strongly toxic first. I emphasise strongly, as many of the plants I note below have compounds in them that can be troublesome. As ever, dosage is everything, and you should take care not to overdo it if a plant comes with a warning.

I recommend you start by reading my post on what constitutes “edible” in the modern world, do your own research, take personal responsibility for your concoctions, and make recipe decisions based on your own unique physiology. I can’t advise you here on what a sensible amount of any particular plant is for you (if you have lots of questions, consider booking me for an online 1-to-1 support session ).

Recommended Reading: The Day I Ate a Deadly Plant: The Spectrum of Edibility

I make a wide range of vermouths. Some I would serve to my granny. Others I keep at the back of the shelf and use sparingly on knowing bitter aficionados! Most fall somewhere in-between, and, as a small part of a small part of a cocktail, pose considerably less threat to heath than the alcohol in which they are suspended.

It should go without saying that even more care should be taken regarding both alcohol and some of these bitter compounds if you are pregnant.

Depending on their flavour profile and cellular structure, some plants give up their flavour better as tinctures (infusion into strong alcohol), some as syrups (infusion into sugar syrup) and some as a direct infusion into the base medium (probably wine). Don’t get too hung up on this to start with – there is plenty of time for process geekery once you’ve found your feet, but to start with you just want to assemble some interesting potions.

Here are just a few wild plants that I recommend playing with. Most are common and have worked well for me in vermouths. I often make complex vermouths with over 50 plants in them, but one with only a handful of well chosen and balanced plants can easily be as good.

Wormwood

Including Grand or Absinthe Wormwood (Artemesia absinthium), Roman Wormwood (A.pontica), and Sea Wormwood (A.maritima), but there are lots of other interesting varieties. See my discussion and photos above.

- Part used: Leaves, (flowers, seeds)

- Flavour profile: bitter/aromatic

- Recommended infusion method: Tincture, but can also be added fresh or dried to base, though quantity can be hard to judge and things can quickly get too bitter. Adding a teaspoon at a time of tincture makes flavour balancing easier.

- Health warnings: Contains thujone

- Notes: Use dry or fresh. While you don’t have to use wormwood in your scratch vermouth, there is a reason it gave its name to the beverage, so worth seeking out.

Mugwort (Artemesia vulgaris)

- Part used: Leaves, buds, flowers

- Flavour profile: Aromatic, menthol?, slightly bitter, though much less so than wormwood

- Recommended infusion method: Tincture or infusion

- Health warnings: Contains thujone

- Notes: Use dry or fresh. Much easier to come across in the wild than wormwood. Said to make you have vivid dreams!

Bog Myrtle (Myrica gale)

- Part used: Leaves, catkins, buds

- Flavour profile: Bitter/aromatic

- Recommended infusion method: Tincture, syrup

- Health warnings: Contains thujone

- Notes: Use fresh if possible. The whole plant smells delectable, but my favourite part is the catkins, which add honey backnotes into an already mind blowing aroma. I use bog myrtle as a key part of fernet style bitters

Wild brewer Pascal Baudar got very excited when I introduced him to bog myrtle on Islay! ©GallowayWildFoods.com

Wood Sage (Teucrium scorodonia)

- Part used: Leaves

- Flavour profile: Bitter/aromatic

- Recommended infusion method: Tincture

- Health warnings: Contains Clerodane diterpenes

- Notes: Fresh or dried. Despite the name, this is also very common near the coast, growing out of rocky bankings

Common hogweed (Heracleum sphondyllium)

- Read all about common hogweed here

- Part used: Schizocarps (seed pods) – green or dry – learn more about them here, or roots

- Flavour profile: Aromatic/bitter/citrus/floral/gingery

- Recommended infusion method: Tincture or syrup

- Health warnings: Read safety notes for handling common hogweed here

- Notes: Complex spicy, citrussy bitters, a bit love-hate!

Common hogweed seeds in their naturally dried state – further drying required when you get them home. ©GallowayWildFoods.com

Sweet Cicely (Myhrris odorata)

- Read all about sweet cicely here

- Part used: Leaves, stems, flowers, schizocarps (seed pods) while still green

- Flavour profile: Sweet anise

- Recommended infusion method: Infusion or syrup

- Health warnings: None – but take extra care with identification – see here.

- Notes: Adds a sweet anise back note, but easily overpowered

Sweet cicely seed casings add wonderful anise flavour. Other parts of the plant work too. ©GallowayWildFoods.com

Wild Angelica (Angelica sylvestris)

- Read more about angelica here

- Part used: Schizocarps (seed pods) green or dry, roots

- Flavour profile: Bitter aromatic, earthy perfume

- Recommended infusion method: Tincture or syrup

- Health warnings: None

- Notes: Angelica root is widely used in gins, vermouths and other aromatic drinks for its rounded harmonic effect on other flavours, and for adding complex back-notes. It is a very common plant in much of the UK, but if you do harvest its root, please do so considerately and legally!

Wild angelica root is amazingly aromatic and hyper abundant across Scotland. Nevertheless, ensure you have the landowner’s permission before uprooting, or harvest a section of root then replant. ©GallowayWildFoods.com

More members of the carrot Family (Apiaceae)

You need to put some work in with this family, but it offers a great many exciting opportunities for vermouth making once you get to know it. Learn more about it here.

Wood Avens (Geum urbanum)

- Read all about Wood Avens here

- Part used: Roots

- Flavour profile: Earthy aromatic, spicy – of cloves. Great spicy back-note

- Recommended infusion method: Tincture or syrup

- Health warnings: None

- Notes: Best to use fresh roots. Tincture for at least 1 month. A very common plant, often treated as a weed. Nevertheless, please only harvest roots considerately and legally!

Yarrow (Achillea millefolium)

- Part used: Leaves, flowers

- Flavour profile: Bitter herbaceous aromatic

- Recommended infusion method: Any

- Health warnings: Contains thujone

- Notes: Fresh or dry

Tansy (Tanacetum vulgare)

- Part used: Leaves, flowers

- Flavour profile: Bitter aromatic

- Recommended infusion method: Any (take care if directly infusing into base medium, as it is potently bitter)

- Health warnings: Contains thujone

- Notes: Drys well, or use fresh. Readily infuses by any method.

Conifers, especially Fir, Spruce and Larch

- Part used: Needles, ideally, but not essentially, new season’s growth

- Flavour profile: Aromatic, citrus, pine, tannic

- Recommended infusion method: Any

- Health warnings: None, provided you avoid yew! See my Drinker’s Guide to Conifers

- Notes: Citrussy/pinene flavours add bright notes to your vermouth, and pair well with gin

Elder (Sambuca negris)

- Read all about Elderflowers and Elderberries here

- Part used: Flowers or berries

- Flavour profile: Flowers – Floral, muscat, vanilla, bananas, Berries – deep, complex sweet red fruit

- Recommended infusion method: Flowers – Any, Berries – Syrup

- Health warnings: Flowers – None, Fruit – contain small amounts of a precursor to hydrogen cyanide. Don’t be unduly alarmed by this – so do apples! Nevertheless, elderberries should not be eaten raw in any kind of quantity so best to use as a syrup in vermouth, ensuring the syrup is simmered for 5 minutes. This denatures the precursor.

- Notes: Lovely to have the scent of elderflower dance above the bitter flavours, the berries add warmth and complex riches to sweet vermouths.

Meadowsweet (Filipendula ulmaria)

- Read all about Meadowsweet here

- Part used: Flowers, seeds, (leaves)

- Flavour profile: Floral, vanilla, almond, hay (watermelon in leaves)

- Recommended infusion method: Syrup, tincture or direct infusion (cold infuse leaves into syrup to capture watermelon flavour without the germoline flavour!)

- Health warnings: Contains coumarin

- Notes: Richly complex

Fruits such as crab apples, sloes, rosehips, rhubarb, japanese knotweed, blackcurrants, strawberries etc can add rounded acidity and fruity depth and work particularly well in sweet vermouths. Gooseberries are excellent in dry vermouths. Tincture, syrup or crush & infuse into base. Be sure to account for the extra acidity of some fruits when balancing your vermouth.

The Triffid Sour – Gin, sweet cicely syrup, clarified Japanese Knotweed, Japanes knotweed vermouth. ©GallowayWildFoods.com

Fungi can be surprisingly good in vermouths, adding warm earthiness and sometime subtle tannic notes. Play around, start with a bit and see what works for you. I’ve had nice results from dried cep infused direct into base, chanterelle tincture, chaga tincture (tannic properties) and especially beefsteak mushroom tincture (tannic, fruity properties). My mushrumami seasoning works in vermouth too.

Seaweed can add richness, salinity, body and umami to your vermouth. Try directly infusing a blade or two of kelp into your base medium. Pepper dulse can add spice and complexity, but don’t heat it, as it will emit a rather unpleasant gas!

More inspiration on exciting spices and flavourings you could use on my Guide to Our Wild Spice Rack.

2. Make tinctures from your chosen botanicals

Foragers with a leaning toward the tipsy side of their craft accumulate tinctures as wood carver might accumulate interesting lumps of wood. On their own, these may be only of passing appeal, but once sculpted into a finished product their inner character is unlocked and allowed to shine. The essence of a glut of something aromatic and interesting can be captured in alcohol before you know quite what to do with it. Just pop a bottle of cheap vodka over it and let it steep. Herbalists call the results of this a tincture. It is the basis of that forager’s classic sloe gin.

Some botanicals tincture well, giving up good flavour to strong alcohol, while some are better infused into your base wine or syrups for sweetening, as outlined above. Some will give up their flavours quicker than others.

Those that work well in tincture should be infused in a neutral base spirit. This should ideally be at least 40% ABV, but that annoying 37.5% ABV that cheap vodkas come in at is fine. In the US pure, or almost pure, rectified spirit alcohols are available, usually under brand names are available, and will give a cleaner extraction of flavours, but these are hard to get hold of in the UK.

How Long to Infuse Botanicals in Alcohol?

This can vary widely according to the nature of the botanical you are steeping and the strength of the alcohol you are using. In general, seeds, fruits and roots take longer than leaves or flowers to infuse. Stronger alcohol will “lift” flavours more quickly and cleanly. But, whatever strength of alcohol you use, if left too long, the alcohol will start to pull apart the botanicals altogether and leave you with a muddy looking, vegetal tasting infusion.

Some trial and error and regular tasting is required to ascertain optimum infusion time with different botanicals. Fragile matter like flowers and shoots tend to give up their flavour quite quickly then soon after that start to deteriorate. So sometimes only an hour or two is necessary; roots, seeds and stone fruits tend to give up their flavour more slowly and be more resistant to breaking down, taking days, weeks or months to reach their best. Don’t fret too much, even over-steeped tinctures can make good vermouth. Enjoy learning the craft and honing your taste buds through regular tastings!

3. Make Syrups with your Chosen Botanicals

A vermouth aromatised with only bitter aromatics will be beyond the enjoyment of all but the bitterest of palates. Even dry vermouths require require some balancing with sweetness. You can decide where on the dry-to-sweet spectum your vermouth ends up by incrementally and adding your choice of sweetener(s):

– Caramel. This is the traditional method for making sweet vermouths. Heat sugar in a pan with a little water until it starts to caramelise. Its your call how deep and “burnt” you wish to take the caramel to.

– Honey can add complex floral dimensions

– Birch sap syrup is my favorite sweetener for vermouth, offering complex sweet and bitter caramel notes. Its very hard won though, and you might want to keep any bottles made with it for “best” (i.e. yourself!)

– Flavoured syrups. My go-to sweetener for many of my bittersweet concoctions is wood avens (Geum urbanum – aka cloveroot) syrup, which lends a warm, spicy bass note. I’ve had good results with other rich, harmonic flavours like burdock, angelica and hogweed root, and floral aromatics like elderflower or meadowsweet. Play around.

Assembling Wild Potions to blend into vermouth, including: Burdock syrup, elderflower syrup and birch syrup. ©GallowayWildFoods.com

4. Select a Base Medium and directly infuse

Usually this will be a decent-but-not-too-expensive white grape wine without too much flavour of its own, but non-grape wines can also work. I often use birch sap wine which gives a warm, soft, neutral base. Gooseberry wine starts you off from a sharp, fruity platform. Beers and ciders can also work – by all means break all rules if you think it might work, but generally look for an ABV of 10 – 14% in your base.

Birch sap, for fermenting into base wine for vermouth – but you can just buy a standard white wine. ©GallowayWildFoods.com

Add your plants for direct infusion to the base. The trick is to heat the base without losing precious alcohol. Alcohol will start to evaporate rapidly at 78ºCelsius (173ºFarenheit). If you have the gear, packaging sous vide (under plastic) and heating in a water bath to about 70% for 45-60 minutes is ideal – or if you’re in a hurry, ziplock and give it a blast in the microwave! If you don’t have a vacuum packer/water bath, a carefully watched pan and thermometer work fine. Hold it at 60 – 70ºC, lid on, for 15 – 30 minutes. Leave the now partially aromatised base to cool.

Infusing base wine with botanicals. Here, magnolia petals, roman wormwood, flowering currant. ©GallowayWildFoods.com

Go easy if you are infusing wormwood – I once made a 6 bottle batch far too bitter for even my taste, even after sweetening. Nothing need be wasted in this process though – I later used each of one those bottles to aromatise 6 more.

You should end up with a tasty, but not overpoweringly bitter aromatised wine, which you can now fortify and intensify.

Infusing base wine with turkey tail, rosehips and spignel. Slightly out of focus, a fair reflection of all the “tasting” i’d already done at this stage! ©GallowayWildFoods.com

4. Fortify with Tinctures

This is the fun bit… Line up all the bitter-aromatic tinctures you have prepared and add them – in a careful and measured way – to the base. If i’m making one or two bottles, I do this with a tablespoon measure, a couple of tablespoons at a time, followed by a stir and a taste.

If you think you might be making a masterpiece, or are of a scientific persuasion, be sure to take note of how much of each tincture you add in relation to your base volume, though personally I prefer to never make the same vermouth twice, no matter how good the last one was! You are looking to bring the alcohol content up to between 16 and 20% ABV. This probably means about 20 – 30 tablespoons at 40% in 750ml of 14% wine. To be honest, I’ve never measured it accurately, preferring to go by taste.

By the end of this process you should have a bitter fortified wine. If you are a real bitter-lover it can be hard to know when to stop! If you are planning a dry vermouth, go easy with the bitters, as if you overdo it you’ll need to add so much sweetness to balance them, your finished product will be far from dry.

5. Sweeten to Taste

You will now have a bitter base that, unless you’ve used a really light touch, is likely to be too much for anyone but bitter extremists. Now you need to temper and dilute that bitterness with sweet liquids.

If you are attempting a dry vermouth, you need to keep the bitterness light in stage 4 so you don’t need to add lots of sweetness at this stage.

Add your syrup(s) from stage 3 carefully, as you did with the tinctures, tasting regularly. Sweetness will temper and soothe the bitter flavours, and add notes of their own. Think of this as adding a softening, coloured filter to a sharp photograph. Keep adding until you are happy with your potion.

By now you may have been tasting quite a lot. You might need to go and have a wee sleep! But seriously – I recommend taking a break as regular tasting of bitters can start to overpower and dull the palate. Leave it for a while, then come back when you can taste clearly again to add the final touches to your masterpiece!

6. Aging, Clarification and Storage

If you want to really pimp your vermouth, you can age it in oak. Oak casks are unlikely to be practical for domestic scale production, but it is possible to add oak chips to kilners of your preparation.

Once happy with the flavour and balance of your vermouth, strain it thoroughly through several layers of muslin, J-cloths or coffee filter.

To achieve a fully clear vermouth its necessary to store it near freezing point (about -8ºC) for several days to precipitate any remaining solids.

Personally I don’t bother – I just let them settle on my shelf and pour gently. You can always decant them if a bit of sediment bothers you.

Once you are happy with the finished product, store in the fridge and use a vacuum cork to prevent oxidation (especially once you start to get down the bottle). Or drink it fast…

Congratulations: you’ve made vermouth!

Remember, if it all seems a bit much, this is not a drink that is generally drunk on its own.

Try it well diluted in a spritzer, or a small measure in a royale in your wild flower champagne. This should reveal more of its nuances and you’ll likely be delighted with your work.

If you’ve made a sweet one, use it to put your personal stamp and terroir on a negroni or manhatten. I often mix mine 1:3 or 1:4 with sloe gin, which adds a rich complexity to a classic.

Wondering what to do with your wild creation?

Here is some inspiration from my Gin Deck…

Move over Corpse Reviver#2, time for the Copse Reviver…Equal parts:Botanist GinForaged vermouthCrab apple…

Posted by Galloway Wild Foods on Friday, 11 November 2016

Been playing with @buckandbirch's delicious Aelder Elixir. This came out real tasty, and with a pretty pink head!Purple…

Posted by Galloway Wild Foods on Monday, 21 November 2016

Best/only good thing about the clocks going back… #sundowners an hour earlier.Rock samphire gin + birch sap vermouth = #wildmartini#wildbooze

Posted by Galloway Wild Foods on Thursday, 2 November 2017

Long Islay Ice Tree.Made with douglas fir @thebotanistgin, foraged vermouth, ground ivy & cloveroot shrub, elderflower…

Posted by Galloway Wild Foods on Monday, 18 April 2016

"Drink of Champignons": chanterelle schnapps, chaga vermouth, spiced cep shrub, oyster mushroom umami seasoning,…

Posted by Galloway Wild Foods on Tuesday, 18 August 2015

A wild #summer #cocktail: Gin infused with cucumber and sea lettuce, with 2 rose soda. Garnish of foraged vermouth-soaked orache & cucumber, sea lettuce & cucumber crisps. #wildfood #wildbooze #gin #cocktails

Posted by Galloway Wild Foods on Friday, 26 June 2015

Wild night in Manhattan.50ml rye whisky15ml japanese knotweed vermouth5ml wild cherry syrupBog myrtle bittersBoozy sloes#wildbooze #cocktails #manhattan #foraging #sundowners

Posted by Galloway Wild Foods on Monday, 23 May 2016

Firgroni time…@northuistdistillery Downpour gin, strawberry & pineapple weed vermouth, green hogseed campari, noble fir bitters.#sundowners #wildbooze#drunkenbotany#negroni

Posted by Galloway Wild Foods on Wednesday, 26 June 2019

After a pleasant hour sloe harvesting, home in time for a #sundowner. The Beano – Very Sloe gin, Galloway vermouth,…

Posted by Galloway Wild Foods on Thursday, 27 September 2018

Firgroni time!Noble fir infused @thebotanistgin , #Galloway sweet vermouth, aperol, tansy bitters.#drunkenbotany#wildbooze#bitearlyforsundowners#negroni#firgroni

Posted by Galloway Wild Foods on Sunday, 13 May 2018

Filthy great @reyka_vodka martini, tansy vermouth.#keepboozeboozy#sundowners#tansy

Posted by Galloway Wild Foods on Saturday, 12 August 2017

Sundowner after a hard day's preserving…The BigsonGin, Galloway blossom vermouth, pickled magnolia hearts.#wildbooze #icallthiswork #sundowners #galloway

Posted by Galloway Wild Foods on Friday, 7 April 2017

Ribes-inaGin, Galloway spring vermouth, flowering currant & japanese knotweed shrub, elderflower & buckthorn champagne.#wildbooze #gindeck #spring #floweringcurrant

Posted by Galloway Wild Foods on Monday, 27 March 2017

Quick play on the gin deck before travels resume…Ben Lomond Gin from my friends on The Loch, with my bog myrtle &…

Posted by Galloway Wild Foods on Tuesday, 13 August 2019

Galloway Summer Cup – every ingredient from within 5 minutes of home. :)- 6 blossom champagne – Sweet lockdown…

Posted by Galloway Wild Foods on Thursday, 25 June 2020

Celebrating the first of this year’s pineapple weed with an elderflower, sweet woodruff & pineapple weed cooler.-…

Posted by Galloway Wild Foods on Tuesday, 26 May 2020

Related Pages:

9 Comments

This is wonderful! I make vermouth from herbs both foraged and purchased. I’ve never done a completely foraged one. Thanks so much for this thorough explanation. I’ve also made amaro with many items from my yard. That was my masterpiece. I even used oak chips to mimic barrel aging. Looking forward to putting even more of of my terroir into the next one.

Thanks so much for a really interesting article. Before I stumbled on your site I was more interested in medicinal foraging and I had never thought of using what I found to make alcohol! Thanks to you I now have a very pretty rose-coloured vermouth in my fridge flavoured with yarrow, wormwood, pine needles, sweet woodruff, rosehip syrup, sloes, meadowsweet and a few dried slices of boletus. I was a little too heavy handed with the meadowsweet since a little goes a long way but that’s the joy of learning.

On a side note your site has also given me food for thought about mushrooms. When I started mushrooming I was told that since mushrooms are just the fruiting bodies of the larger organism, picking baby mushrooms is no worse than picking an unripe apple (and far more fiddly) and picking lots of large mushrooms is fine, since they will have spored anyway. After reading your articles on the subject I’m still unsure about the biology but I’ve decided to err on the side of caution and avoid over picking.

Thanks Jade, glad you found it interesting, and are enjoying some wild booze adventures! One mistake that people can fall into with regard to harvesting mushrooms sustainably, is in assuming that all species are the same! Fungi are as – if not more – diverse than plants, so there are no “one-size-fits-all” rules for all species. Intimacy (ie. really getting to know your quarry) and respect are the main things, but, in general, I always think that, provided its mushrooms have reached spore-bearing maturity, most fungi would thank you for picking them and moving them around the forest, cap-down, in an open-weave basket. Thus you become a vector and helper in spreading spores. In the huge Galloway Forest where I live, its no coincidence that the biggest numbers and largest variety of fungi occur in the areas that most humans visit… 🙂

Mark

Thank you for this, it’s super helpful! I’m about to try my hand at making my own aromatic bitters and so much of this information is transferable to that, but I have decided that I will experiment a bit with vermouth as well.

I have a question, do you ever use dandelion root in any of these? How does it compare in flavour to things like wormwood or mugwort when infused in alcohol?

All the recipes for aromatic bitters use gentian root and quassia bark but there is none of that around here, and I am not familiar with mugwort, so I won’t go out searching for it this time.

There are plenty of other bitters/aromatics around me (bog myrtle, wood sage, spruce, last year’s hogseeds etc.) but I think for aromatic bitters I will need something with a punch.

Thanks in advance for any replies!

I don’t use dandelion root, but it would definitely work. Angelica root is also excellent.

Hi Mark

Thank you for this delicious site. Can I use mugwort root for the liqueur?

Thanks in advance

I haven’t tried it, but don’t see why not. 🙂

Dear Mark..

I loved this article as I have been foraging ever since I read Richard Mabey’s Food for Free in 1974!!!

I have been making country wines with Foraged ingredients for many years and every year can’t resist making another few gallons of dandelion wine… Trying to get it fairly dry and as strong as possible.. For a few years now I have been interested in making my own Vermouth as like you drinking is a mammoth pleasure.. And because good Vermouth.. Is expensive..

Making Vermouth is so incredibly complicated.. You have to become an Apothecary…

Hardly surprising the commercial brands keep their recipes a secret..

I have been reading about Vermouth ingredients and trying different ingredients myself.. Like you.. For quite a while now.. But I can’t get anywhere near the taste of for example.. Dollin, Noilly Prat.. Or Martini..

Thanks again for a great article which I am saving…

Would love to try some of yours and love the idea of seaweed and also funghi..

By the way Fly Agaric.. Known to be like Death Cap.. Fatally poisonous… Is there a part of that funghi that is edible??

All the best

Regards Tim

Hi Tim,

Thanks for all of this. Its always nice to compare notes with a fellow drunken botanist! Do drop me an email to explore swaps/compare notes. Dry vermouths are hard to emulate. You can read an in depth article on fly agaric and its uses etc on my website here:

Cheers

Mark.