Laver Seaweed – Edibility, Identification, Distribution, Preparation, Usage and Laverbread Recipe

Porphyra spp. aka. Nori, Slake (A number of different porphyra species are common and used in similar ways – see below for more info)

- Identification – 4/5 – Easily recognised: deep brown/green/purple sheets, looking like stranded black (or occasionally dull, dark greenish) bin bags when the tide is out. See below for notes on different species.

- Edibility – 4/5 – A great ingredient and important member any wild food larder

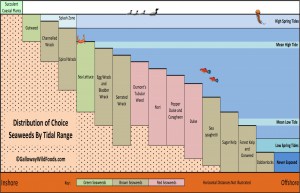

- Habitat – Clinging to moderately exposed rocks on open beaches, from about half to two thirds of the way down the tidal range. Also on groins, piers and harbour walls. Habitat varies according to the species of porphyra you encounter.

- Distribution – 3/5 – UK-wide but occasional and a little picky about where it will grow

- Season – One or another species of larver are likely to be available at most times of year, but its mostly at its best for harvesting November – July.

- How to harvest – Mindfully harvested by cutting (never pulling) up to 2/3rds of the growing sheets, leaving plenty connected to the rock, and never clearing a whole rock or area. Don’t be put off if it clings to the rocks in dry mats – it soon rehydrates. Gathered on a receding tide it will be easier to clean.

- How to eat – Dried, toasted and crumbled as a seasoning for rice, salads, stir-fries etc and in stock powders; Or cooked, as an enricher of soups, stews etc; As a rich textural addition to pies, tarts etc; Mixed (after simmering) with oatmeal and fried as patties to make laverbread; as the core ingredient of very “meaty” tasting vegan patés; the drained cooking liquor makes a thick, umami-rich stock.

Laver has no great flavour if you eat it raw, but once processed, imparts a rich, savoury, umami quality to anything it is added to. I have not found a single savoury dish that can’t be improved by its addition and it is a cornerstone of my wild larder.

Varieties of Laver

Those of a geeky disposition will be interested to know that several species of laver – porphyra – are indigenous to UK waters, all of them edible and of more or less similar culinary merits. So all the following species can be treated in the ways I describe below.

Several species of laver are indigenous to the North Atlantic and even marine biologists can struggle to tell them apart. Without resorting to microscopy, habitat and gestalt (that is, the general “vibe” of the seaweed) are often the best clues. Misidentification isn’t problematic in the benign world of seaweeds, and all laver species have similar culinary merits, though some take a good deal more effort to harvest than others. All can be treated in the ways I describe below. Here are the four you are most likely to encounter.

Purple laver (Porphyra pupurea) is the largest of the lavers, with silky textured blades with ruffled edges growing up 1 metre/3ft long and 20cm/8 inches wide. It grows on rocks in the mid tidal range in exposed locations, often covering them like melted black bin bags. It is black with hints of purple in winter, looking more blackish-green as the year progresses. This is the most efficient species to harvest due to its large size.

Tough Laver (Porphyra umbilicalis) is smaller, with a slightly tougher texture and generally found on the upper tidal range.

Winter laver (Porphyra linearis) has narrow blades and is only found in winter months.

Pale patch laver (Neopyropia leucosticta) can be found clinging as an epiphyte to grape pip weed and serrated wrack.

Another species of laver – P. yezwensis – does not grow wild around the UK, but is the variety you are most likely to encounter wrapped around sushi and labelled by its Japanese moniker, nori. It is farmed and harvested commercially in vast quantities around Japan.

Check out my Seaweed Webinar which includes an in-depth 20 minute film on laver identification, harvesting, processing, cookery and a recipe demonstration of making laverbread.

“The webinar was amazing! You are a good storyteller. Scientific information, combined with tips and beautiful picturing. 👏” – Kanlenaki on Instagram

“This was absolutely brilliant, thank you so very much for being so generous with your knowledge! The webinar format of videos and live worked fantastically!” – Sarah Hobbs, Webinar chat comments

I have made several, admittedly half-hearted, attempts to make nori sheets from our indigenous porphyra species to serve around my wild sushi. The most successful efforts came out more like (tasty!) fish-net tights than anything that might hold rice. I’ve given up, but I have seen some respectable efforts from my friend Monica Wilde (who has rather more of an eye for detail than me). Hers came out like dark, brittle cardboard, great for breaking up and serving tit-bits on, but never likely to embrace anything. The undisputed master of sushi paper making (and all sorts of wild paper making) in the UK is Fergus Drennan – read his beautiful rambling blog on the subject here.

Cleaning, Preparing, Cooking and Drying Laver

For a deep dive into using laver in the kitchen, see my Seaweed Webinar.

Once harvested, most of the work is in rinsing out the sand and silt. Don’t rush this job – my friend gave me a jars of smoked dried laver that tasted fantastic (seaweeds and smoke are natural bedfellows), but was basically unusable because it was full of silty sand. The most delicious of things can be rendered quite unpleasant by only a small amount of sandy crunch!

Collecting in net bags and rinsing thoroughly in clean sea water before you take it home is a good start, but you’ll also need use plenty of changes of cold fresh water once you get it to your kitchen. I put fat handfuls into the basket of a salad spinner, and run cold water through them, before sitting the basket in its spinner, filling with water and swirling it round (while still full of water), before draining, spinning off excess water and then repeating the whole process. By checking the bottom of the water after each spin, you can monitor how much sand/silt remains. Usually repeating this method about five times is enough.

I then pack the spun, squeezed-out laver onto shelves of my dehydrator. On fine spring days, i’ll leave these out in the sun to begin the drying process, but (unless you do separate out the individual sheets, and/or have a really warm, breezy day), they won’t fully dry like this (remember that laver has evolved to resist drying out at low tide by forming an “outer crust” while trapping plenty of moisture between its sheets below).

Provided you have a good dehydrator don’t worry about separating out individual sheets. You can also use a fan oven on its lowest possible heat setting (perhaps with the door left slightly ajar) or anywhere warm with good air flow.

Fully dehydrated laver “blocks”. In this state they can be stored almost indefinitely in airtight containers, for later use

Laver goes chewy and awkward to use when you simply dry it like this, but, once dried, a little toasting in the oven or in a dry frying pan works magic, turning it slightly green and bringing out the deeply savoury nori flavour you will be familiar with in Japanese cuisine and seaweed snacks. Don’t over toast it as it can go over and burn very quickly at which point it becomes unpleasantly bitter.

Ground to a fine powder, dried, toasted laver is one of the most useful additions to any forager’s wild pantry, imparting rich umami to anything it is sprinkled on, or added to shortcrust pastry or sourdough bread. Paired with dried cep powder, it becomes a supercharged savoury weapon of mass deliciousness, and enhances any savoury dish to which it is added.

Insta-dashi stock before shaking. Made with dried, powdered ceps, cauliflower fungus, orange birch bolete, gutweed, pepper dulse and laver

To cook laver from fresh or dry, place in a pan with fresh water – just a little if the laver is fresh or already rehydrated, as it will exude plenty more water as it cooks, but more water if it is dried to allow for rehydration. Then bring to a simmer and cook on just enough heat to keep it “blipping”, with a lid on, for about 3 hours, ensuring it doesn’t boil dry. Just add more water if you think its necessary. You can reduce the cooking time a little, and improve the keeping qualities of the cooked seaweed, by adding a little apple cider vinegar to the pan.

Once the laver is very soft, drain and squeeze it out, taking care to reserve the liquid which is the richest, most umami and nutrient rich stock you could imagine. Reduce the stock down further once you’ve removed the seaweed to make a concentrate and freeze it in ice cube trays for throwing into sauces or making a glaze for meat.

The paste you are left with after straining is what is sold in Wales as laverbread. If you aren’t planning to use it all right away, put the cooked, drained laver in small tubs or ziplocks in the freezer (it doesn’t keep very well unfrozen). This is a great freezer resource, which I bring out to add to savoury richness and body to stews and soups, as a filling for tarts, in mushroom/vegy/vegan patés and as a layer in mile-high wild pie.

Laverbread Burgers Recipe

For a demonstration of laverbread making, see my seaweed webinar.

While the paste is technically the “laverbread”, the term is often also applied to fried patties. For the avoidance of confusion I refer to these as laverbread burgers.

Blitz the cooked, strained laver with a stick blender or in a food processor then add pinhead oatmeal (I use medium, but you could use fine or coarse oatmeal, or rolled oats, or a mixture), until it becomes thick enough to roughly mould into patties. Between a half and equal volumes of oatmeal to laver is about right. Unusually for seaweed, you may wish to add some seasoning – depending on my mood, I add some or all of:soy sauce, miso paste, mushrumami “soy” sauce, spoot clam garum, pepper dulse, sun-dried white sea lettuce and fermented wild garlic. A bit of the liquid from a ferment or a the juice of a lemon or two add a nice bit of acidity – and I sometimes use ponzu shoyu, delicious citrussy soy sauce if I’m feeling decedent. You can also pimp them with chopped wild garlic, or mushrooms. Whatever takes your fancy really.

Leave the mix for at least an hour, or better still, overnight, to allow the oatmeal to swell up. This will make it easier to form patties, as will wetted hands.

Shallow fry the patties in a fat of your choosing. Bacon fat it the acme of frying mediums for laverbread, but they are still extremely good fried in less decadent fats. It should be hot but not smoking.

Press them with the back of a spatula to a thickness you like as they fry, until the oatmeal starts to bronze and form a nice crust.

I make them in huge batches, then once cool, IQF freeze them (ie. lay them on trays in the freezer so the patties aren’t touching, then once frozen move them into tubs. Stored this way, you can take them out and reheat them in the oven as you need them. This is very practical, but do be sure to eat some freshly fried when the the oatmeal is still bronzed and crispy on the outside!

I like hot laverbread with smoked fish and sea beet for breakfast. They are often served with cockles or mussels, and I particularly enjoy them in a deep, deep umami-fest with very lightly steamed razor clams. These are top notch “grows-together, goes-together” pairings, but don’t feel restricted to marine themes. They are also delicious served cold, maybe for dipping in wild garlic pesto or alongside nettle soup.

eared roe deer liver with laverbread, chrain, ground elder, wild leeks, reindeer moss, elderberry, gorse

Related pages:

29 Comments

Thanks for the very informative article. I’d be interested to know a bit more about the drying process – how thinly you spread it, whether you use sun or wind etc – my motivation is that we have just finished simmering about 8 kilos and its going to eat up a lot of our freezer space.

Hi Mike, I use a dehydrator. I spread the seaweed on silicon mats so it doesn’t stick. The thinner you spread it, the quicker it dries. Cooked laver goes off very quickly unless it is frozen or rapidly (and thoroughly) dehydrated. Best wishes,

Mark.

Can you just dry it and use it as a garnish, as opposed to boiling?

Yes, though you’d probably want to grind it to powder after drying. Can be quite tough.

I just wash and then dry it fresh without cooking in my dehydrator, then it’s in my high power blender, ( it’s very tough) as small flakes i use a three fingered pinch in most of my casseroles and sauces. I have just renewed my years supply which is about 500 grams dry weight, which took me about 10 minutes to pick, and 1 hour to dry and prepare.

It’s funny to me that you say it has no flavour. I find it very flavoursome, a taste all of it’s own. It might be the difference in cooking. Cooking sloke, as we call it here in Ireland, as you say involves a lot of washing to remove all the sand. You might like to try my method(actually my grandfathers’) A good knob of butter in a heavy pan, add the laver a handful at a time, squeezing out as much water as you can before adding to the pot, fry in the butter until it reduces in volume, then add some more until your bucket full is added to the pot. Continue sweating the laver down until it is about half a pot full, pounding with a wooden spoon all the time, if it was long, cut with scissors. Then add boiling water until it doubles in size, cover and simmer for 4 hours. Eaten cold with hot spuds. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_kZQDsXLOEI

Does groin mean something different to you than it does to me? Because we don’t usually have seaweed on our groins over here in the U.S. : )

I think you do have seaweed on *some* of your groynes/groins… https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Groyne

Hi Mark

I’m really enjoying your seaweed content, out of everywhere I’ve searched on the internet yours is the most comprehensive. I’m based in North Cornwall and I’ve recently got into harvesting small amounts of seaweed very local to my house during the lockdown. I’m struggling to notice the difference between Laver and Sea Lettuce, do they grow on the same rock, often with the laver on top? This is how it seems to me, the bright green thinner pieces underneath or around look like thin sea lettuce and the brown thicker pieces (but never as thick as what I search on the internet) grow on top.

Any help appreciated, regards.

Hi Max,

Sea lettuce can certainly lurk under other seaweeds. It should be vibrant green v laver, with its dark purplish – black – deep olive green colour, according to the species you have, and the condition it is in. Laver is usually very thin. The two species are closely related, and can be used in similar ways, so not a big worry if you mix them up. 🙂

Mark

I’ve just been harvesting at Porthtowan in North Cornwall and seen what you describe..

Basically it looks to me like the strands of bright green sea lettuce-like weed has attached to and grown itself from the ends of the dark greeny brownish laver/nori.

Not seen this before, so was struck by your mentioning it!

Also, it was only like this on the western end of the beach. At the eastern end, the laver was much thicker, longer and blacker and without the green weed attachments to it.

Wonder what’s afoot with this..

Why has my freshly picked laver turned to a dark green after 5 hours of boiling?

This is normal, and can vary depending on the exact species of laver you have, and how mature it was when you harvested. Nothing to worry about.

Thanks Mark first time l have picked any for about 50 yrs,a lot cheaper than buying it.A lot of work involved but worth every bit.

Hello….firstly a brilliant site .well done….wondered if I could ask a question though . The washing of laver. Is there a trick to getting sand out.i spend ages with it under the tap in a collinder. Still to find sand in and result……was thinking of a kids paddling pool with clean water and give it a good swirling…..any info would be greatly appreciated

A big sink full of cold water, much swirling, rinsing, and then repeating the process until it is sand free – the only way i’m afraid!

Brilliant site Mark! To clarify, when you dehydrate your laver do you cook it first, or dry it from fresh? So is it: cook, drain, dry, toast, powder? Thank you, Tim

Hi Tim,

I dry it from fresh (ie. unchecked, but after extensive washing, rinsing, spinning/wringing). I dry it in big crumply shelf-fulls in my dehydrator (no need to faff about separating individual sheets/pieces provided you have a good dehydrator). The resulting “blocks” can be stored almost indefinitely, then cooked in water to make laverbread, or toasted (the whole “block”) in the oven then ground as seasoning powder – or any other process.

Mark

Thanks for very informative site. I got a taste for Laver growing up in Barnstaple as a kid. Fifty years ago Butchers row was just butchers shops and all sold Laver, nowadays you struggle to buy it. I have been picking Laver for a couple of years but one question still eludes me, I am sure that Laver has Vinegar added to it, firstly is this correct and if so when is vinegar added? I found a slow cooker recipe and they said six litres of Laver and 150mm of Cider vinegar but when vinegar is added the Laver tends to release all its moisture, it kind of cures it. I’m now thinking that it should be cooked then seasoned and vinegar added at the end.

I would be interested to hear others thoughts. Take care.

Thanks Ian – its interesting to hear that it was sold in butcher’s shops.

You might have missed in my text, but a little (apple cider) vinegar added during the simmering reduces the cooking time and slightly improves the keeping qualities.

Mark.

Hi Mark, thank you for sharing such interesting information. I would be interested in a study trip to see the laver seaweed , how it is harvested and prepared . Where are the best places to see this in UK if I have 3 days , could you recommend an itinerary ? Thank you

I could take you to meet laver, and lots of other seaweeds. Best to read the info on my ‘PRIVATE BOOKINGS’ page, then email me. https://gallowaywildfoods.com/learn-to-forage/about/

Hi Mark,

What drying rack do you have, or is there one you would recommend?

Thanks for all this great info!

Best wishes,

Monique

I use an Excalibur with 7 shelves. Excalibur make pretty much the best dehydrators, though pretty expensive and you can get something very nearly as good for about half the price. I discuss dehydrators in my Seaweed Webinar here: https://gallowaywildfoods.com/product/recorded-webinar-a-foragers-guide-to-seaweeds/

I have bought a pressure cooker to cook my laver. I’m from South Wales where unlike North Devon no vinegar is added to the laver. In my experience getting rid of the sand is very very difficult. No laver in North Devon at present, I’m told then only producer is unwell. I’ve tried tinned and vac packed but they’re poor substitutes.

Hi,

I’m based in North Devon and not particularly mobile. Do you know where I can buy laver as the local shops don’t seem to sell it anymore.

Maybe try shopping for it online?

Heards in Westward Ho! oftentimes have it in. As, I believe, do Grattons in Barnstaple.

Thank you for the fabulous walk, the amazing food and all the knowledge.

I found a quantity of laver and today I used your recipe. Oh, the umami!

I found some sugar kelp on an extreme low tide walk and made crisps to go along.

Thank you, thank you, thank you!