Pheasant Kiev Recipe

Way back in the early ’80’s, one of my family’s favourite Saturday supper treats was chicken kiev. Like so much 80’s food, these were a heavily processed, plastic-packed, frozen, pop-in-the oven convenience food, that didn’t even pay lip service to provenance or animal welfare. Textured, reformed, mashed, miserable and mechanically recovered battery chicken, filled with a blob of garlic butter, breaded, fried and frozen for our convenience. In our house they were reheated then scoffed with great delight in front of The Generation Game or Russ Abbot’s Saturday Madhouse, and usually followed by that absolute pinnacle of 80’s decadence – a Vienetta. (I remember getting the tape measure out for the “you cut, I pick” portioning of the Vienetta between my siblings and I. Always a tense moment).

Such convenience food indulgences might seem pretty wrong now, but those were igno-cent times (well, I was only 10), and dodgy chicken kiev was a Saturday treat we all loved. The ooze of greasy garlic through the chicken and fried crumb felt decadent and indulgent, and my teenage brain, perhaps in one of its earliest awakenings to the marvel of cookery, often wondered how they got that magic goo into the middle.

Fast forward 40 years and I’d like to say that we have come a long way in terms of food quality and animal welfare. But a quick google of chicken kiev shows me that this may be more of a change in my own perspective and taste than any significant change in popular food culture. Pre-packaged chicken kievs are still so popular that they are included in the standardised UK grocery basket used to calculate inflation rates. The packaging may be slicker, the messaging more misleading, but there is still no shortage of worryingly cheap heavily packaged chicken kievs out there on stupormarket shelves.

While the traditional use of the term kiev after a meat (usually chicken) generally refers to a stuffing of butter and garlic/herbs, the term has been adopted and adapted to refer to other sauce-stuffed meat (still usually chicken, or something passed of as such), so you can now buy “cheese and ham chicken kiev” and other variants.

For those interested in food history, chicken kiev has a long and noble, if somewhat muddled, gastronomic history. The Russian term kotleta de-voliay referred to any stuffed chicken cutlet and became popular in the late 19th Century, but seems to have its origins in the classical French cookery term côtelette de volaille, which is used to refer to any chicken cutlet dish. Originally these would be stuffed with duxelles of meaty, possibly mushroomy, stuffing, bound with cream and butter. My stuffed pheasant breasts are technically a variant of côtelette à la Maréchale, which is the same technique applied to game birds rather than chicken, though confusingly à la Maréchale is also used to describe meat that is egg-dipped, breaded, sautéed – a technique known as à l’anglaise – English style.

Its not clear when or where herb-infused butter replaced the traditional stuffings, but it isn’t a great leap of ingenuity for a chef, so it seems likely that it may have several origins. What’s clear is that the dish “chicken cutlets Kiev-style” became popular in Russian restaurants in the early 20th Century. In the 1940’s the term chicken kiev survived an attempt by communist food writers and later the Soviet Ministry of Food to replace French-style “bourgeois” names with simple “proletarian” forms. In particular, the “cutlet Kiev-style” was to be renamed “chicken cutlet stuffed with butter”.

The definitive modern chicken kiev would see the boned, skinned breast split lengthways, pounded flat, then stuffed with butter. In Russia the butter alone is sufficient, perhaps with some parsley and dill. The addition of garlic is a more western preference.

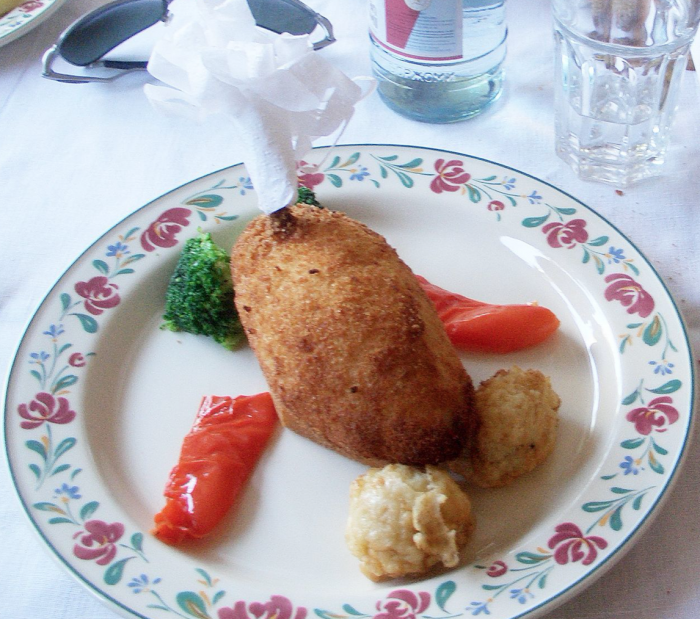

Chicken Kiev, as served in a Kiev restaurant. Note the wing bone is left attached and covered with a manchette.

My personal journey with food has come quite far since our family pig-outs of the 80’s (though i’ll never move on from Monster Munch!), and i’d pretty much forgotten about this childhood pleasure until I was gifted a load of free pheasants from our local shoot, and started looking at different ways to cook them.

I’d been running some free workshops on how to source and process local game for our local climate change action/resilience group. Pheasants are reared and shot for sport all around our valley, and although i’m not personally keen on the shooting of imported and fed birds for fun, it happens and isn’t going away, so there is a surplus of free-range local protein in our valley between the start of October and February each year. During this period pheasants can be obtained for pennies (30p a brace seems to come up a lot) or often for free, and while I wouldn’t choose to actively support sport shooting, it seems to me churlish and wasteful not to make use of their by-products as a source of low-impact, free range local protein. Many shoots are happy to supply birds if you reach out to them. All you need is the time, commitment and (a little) skill to handle, prepare and cook the birds that will arrive whole – guts, feathers, feet and perhaps the odd pellet of shot.

Lead Shot in Pheasants

Shot in pheasants can be more than just an inconvenience, as most UK shoots still use lead shot. The Food Standards Agency clearly states that “Eating lead-shot game meat on a frequent basis can expose you to potentially harmful levels of lead” and that” toddlers, children, pregnant women and women trying for a baby should not eat lead shot game”. As they say: “Anyone who eats lead-shot game should be aware of the risks posed by consuming large amounts of lead”.

This is sound advice, but does beg the question “what constitutes a “large amount”? Only you can really decide this. Personally I am very happy to continue consuming a few brace of pheasants per year. I examine them for shot as I butcher them (you can often locate it by the blood stains in the flesh). Even if a pellet slips through, the chances of swallowing a lead pellet are pretty slim. More likely you will have an unpleasant tooth-crunch experience. I suppose micro quantities of lead “dust” may make their way into your digestive system, but unless you are eating pheasant on a regular and year-round basis, its hard to imagine this amounting to “large amounts”.

Lead shot issues aside, pheasant meat gets mixed reviews. Although full of flavour, it can have a tendency to dry out if not carefully cooked, and is usually somewhat firmer in texture than the fast-reared chickens that our mollycoddled modern palates have become accustomed to.

Pheasant breasts stuffed with wild garlic, goat cheese and hazelnut pesto, seasoned with smoked hen of the woods powder & wrack syphon weed, and ready to be panéd.

So, drawing on this strange mixture of nostalgia for fried convenience food, and a desire to use a surplus local protein, I started making pheasant kievs, stuffing the breast with wild garlic pesto. Although in the UK pheasant season (Oct-Feb) doesn’t much overlap with wild garlic season (March – June unless you happen to live in mild coastal locations such as Galloway, it can be found from December), its worth keeping some by in the freezer from the previous season for this recipe.

Its no great leap of the imagination to adapt this technique to a variety of (wild) fillings, several with a more natural seasonal overlap, and i’ve included them with the recipe below. Using fermented wild garlic adds a pleasing funky acidity, though is quite far from the unctuous buttery indulgence of the original. Play around with your own wild fillings, using what is abundant, in-season or in your-freezer!

I made pheasant kiev for 40 foraging teachers at our annual meet-up of the the Association of Foragers one year. We made a pheasant kiev production-line over wild aperitifs – one person butchering the birds, the next making the pockets, the next stuffing them, then four more for the panéing process. A memorable production line – communal cooking is so much fun, especially lubricated with wild cocktails.

Please don’t be put off by the faff of panéing. I consider myself a fairly lazy cook, but it is absolutely worth the trouble, especially if you prepare large batches for freezing.

I freeze the fully stuffed, egged, breaded and fried breasts individually, so they can be taken out for Saturday night suppers…just like the olden days! Oven cooked from frozen works well, but you should definitely eat some freshly fried to enjoy the breadcrumb coating at its crispest.

They are great with a wild(ish) winter salad of pink purslane, sea radish, wild leeks and scurvy grass.

Don’t be shy with the oil when frying.

Ingredients

- Pheasant breasts, skinned and with all fat removed (don’t be tempted to leave fat on to make them more succulent – pheasant fat is horrible). Ideally nice plump breasts, though smaller ones can be split lengthways, beaten out flat and wrapped around the filling instead of being stuffed – a technique closer to the classical origins of chicken kiev. If you haven’t worked with whole pheasants before, don’t worry – removing the breasts is quick and easy, and doesn’t require you to get involved with any laborious gutting or plucking. Here is a good video to show you how its done. (By the way, pheasant legs are scrawny and full of wirey tendons, but they can still be removed in a similarly efficient manner, then slow/pressure cooked, pulled and used for all manner of good things)

- Wild garlic pesto, or any other wild herb pesto – frozen. Or you can be more classical and make wild garlic butter, but don’t cook the wild garlic in the butter before hand, or its volatile flavours will be lost – keep it raw so it releases its flavour into the pheasant as it cooks). Other successful stuffings include wild mushroom paté (or just cooked chopped mushrooms – velvet shanks, oyster mushrooms and scarlet elf cups are about during pheasant season), and seaweed butter – the meatiness of dulse works very well. Whichever of these you use, its best to freeze it first as it makes it easier to cut and stuff into the breasts. I’ve also had great success stuffing the breasts with lacto-fermented wild greens (especially wild garlic/wild leeks/garlic mustard) – no need to freeze these.

- Optional – Dried wild mushroom powder – ideally made with cep

- Optional – Dried seaweed powder – ideally made with one or all of dulse/pepper dulse/wrack syphon weed

- Optional – Dehydrated fermented wild garlic – this is a fantastic umami seasoning

- Salt and pepper

- Plain flour

- Eggs

- Breadcrumbs. These are best accumulated in your freezer from stale cuts, though bought panko breadcrumbs are great as they tend to go crisper and absorb less fat on frying – worth the indulgence.

- Plenty of low-flavour oil for frying

Method:

Lay a breast on a chopping board and use a small sharp knife to make a deep pocket inside the breast. The easiest way is to push the point of a small, pointed knife into the fat end, keep going halfway into the fillet. Be careful not to cut all the way through or the butter will leak out when cooking. Extend the pocket as far down the fillet as you can, without making it into an open gash.

Repeat with the remaining breasts.

Cut your frozen pesto/herb butter/paté in chunks that match the shape and size of the pockets you cut. If using a femrent, just stuff it in.

Lay out 3 shallow bowls for the panéing process.

In the first add a shallow layer of flour, and add salt and pepper to taste. If you are using dried mushroom/seaweed/fermented wild garlic powder, mix this through the flour too, or, sprinkle it on the breasts before you start.

In the second bowl crack and whisk an egg, maybe two. You can always add more if you get through it.

In the third add your breadcrumbs in a thick layer.

To pané, press both sides of each breast into the flour/seasoning mix, then wallow it in the beaten egg, and finally press it into the breadcrumbs until it is well covered. Its great to have a second pair of hands to help with this process – the first person flouring with one hand and egging with the other, and the second doing the breadcumbing, leaving one hand free for sipping cocktails.

Repeat this process for all the stuffed breasts.

Pour your chosen cooking oil in a thick-bottomed frying pan until it is at least 1cm deep and bring to a medium heat – definitely not smoking hot, or the breadcrumbs will burn long before the pheasant is cooked through. Drop in a large breadcrumb or two to ensure it sizzles gently. Don’t skimp with the oil – you want it to reach pretty much half way up your pheasant breasts.

Carefully lay the breadcrumbed breasts in the hot fat and cook for about 6 minutes each side, or until the breadcrumbs are a rich golden colour. Don’t worry if a little of the stuffing melts and finds it way out into the pan – its still basting the meat from the inside out.

The breadcrumbs will absorb some oil, so if you are doing several batches, be sure to top the oil up and get it back up to temperature between cooks.

If the breasts are large, you may need finish them in a moderate (160˚C) oven. The protection afforded by the panéing process will keep them from drying out.

If you’ve cooked lots with the intention of freezing some, let them fully cool before freezing them individually (so the don’t all freeze onto one another), then tub them up.

You may also be interested in:

- Recipe: Braised pheasant breast with winter chanterelles

- Pheasants

- Wild Garlic, Goat’s Cheese and Hazelnut Pesto Recipe

- How to Ferment Wild Greens Easily

- Wild Food recipes

- Foraging Perspectives: Foraging and Food in 1950’s Russia